Michelangelo, the Eternal Genius

Michelangelo Buonarroti-Simoni was born on March 6, 1475 in Caprese, Italy in Tuscany , about sixty miles east of Florence. A month later his father moved the family back to the Tuscan capital. Ludovico Buonarroti’s family were bankers and money lenders and despite the failure of the family bank, Michelangelo’s father managed assets and property that allowed an upper middle class existence. He occasionally served as a bureaucrat and at the time of Michelangelo’s birth he was assigned to Caprese as an administrator within the local government.

in November of 1497, Michelangelo set out for Carrara and the marble quarries there that supplied the legendary stone for the region’s most important art works. In his possession, he had a letter of introduction from the French cardinal to help him to procure the most magnificent marble available. Michelangelo’s personal visit to Carrara was highly unusual, most customers merely ordered a certain amount of stone and had it shipped to Rome or Florence. It would take six months before Michelangelo selected an appropriate block of material and it was not until August of 1498 that Michelangelo began work on his next project: The Pieta, a portrayal of Mary mourning the death of her crucified son, Jesus Christ.

Despite the success of the Pieta, Michelangelo decided to return to Florence in the Spring of 1501. The specifics are not known but certainly his father would have encouraged such a move and the political climate would have quieted greatly after the removal and execution of Savonarola and the installation of a more stable government. Perhaps Michelangelo might have heard rumors that a major commission might soon be awarded concerning an ongoing project of the Overseers of the Office of Works of Florence Cathedral, The Operai. This project was a series of Old Testament statues that were to adorn the exterior of the cathedral. A figure of Joshua was sculpted by Donatello in 1410, and another figure of Hercules was added in 1463. The Overseers then attempted to commission a sculpture of David, but the project ran into continual obstacles including the death of Donatello and by 1500, the massive block of marble intended to be the statue lay unfinished outside of the cathedral workshop. Concerned that the valuable piece of stone would be damaged by continual exposure, the Operai decided to commission Michelangelo to finish the project. He began work on September 13, 1501. As the work progressed, one obvious problem presented itself. Initially meant for the roof of the cathedral, the statue even when finished would weigh over six tons. It couldn’t possibly be successfully lifted off of the ground. The statue, with obvious symbolic overtones concerning the recent expulsion of the Medici and the establishment of a democracy, could be seen as a powerful statement of the determination of the small city-state to repel any incursion by its powerful neighbors. Upon completion in May of 1504, the statue was placed in front of the then Palazzo della Signoria (today’s Palazzo Vecchio). With its piercing glare turned in the direction of Rome as well as the Medici who were already scheming to retake control of the city, the David initially served a political purpose.

Michelangelo is said to have delivered the finished painting with a note requesting the payment of seventy ducats, Doni, a wealthy but financially astute merchant, sent back forty. A typical artwork of this type would usually cost about ten ducats and Doni reasoned that forty was already a very fair price. Michelangelo responded by demanding either one hundred ducats or the return of the painting. Since Doni was happy with the work and it was meant to commemorate his marriage, he gave Michelangelo his original asking price of seventy ducats. This time, Michelangelo demanded double the original price, one hundred and forty ducats. Supposedly, Doni grudgingly paid up. Such a tale is indicative of the self-image that the artist had developed as no mere tradesman.

Although he was always preoccupied with money and would have personal issues that impacted his output, Michelangelo would never have to struggle for work or commissions again. In fact his reputation spread to the point where rulers of Venice, France and even Turkey attempted to retain his services. All of these attempts failed. However, during this time period a group of Flemish merchants were able to get Michelangelo’s attention and obtain the remarkable Bruges Madonna. They did it by secretly outbidding Pope Julius II. Unlike the Pieta, this statue depicts a younger Virgin and infant Jesus. Approximately six feet tall, this ornate statue features much of the same intricate detail of the Pieta. It also achieved the same artistic profile as some of Michelangelo’s most coveted and prestigious works. The only Michelangelo sculpture to leave Italy during the artist’s lifetime, it was first seized by the French when Bruges was successfully invaded in 1794 and Napoleon decided that he would enjoy its company. It was returned in 1815. The Nazis also stole it in 1944, luckily it was not damaged before being retrieved by the Monuments Men from Hitler’s stash cave at Altaussee, Austria.

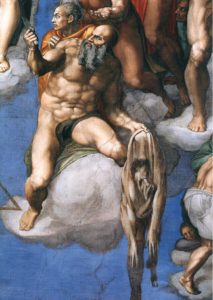

1508 would bring Michelangelo the most challenging assignment of his life. He was paid 500 ducats by Julius to paint the ceiling of the chapel of Pope Sixtus, the Sistine Chapel.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS