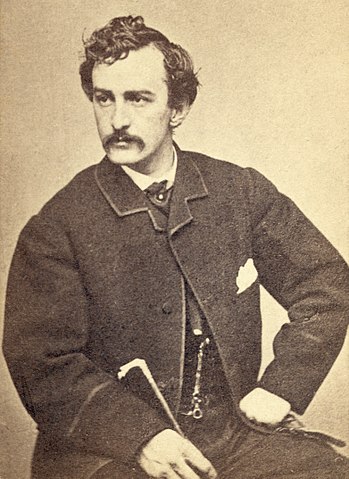

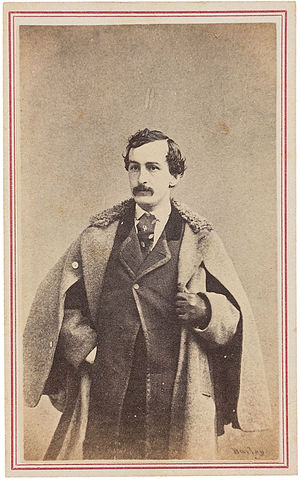

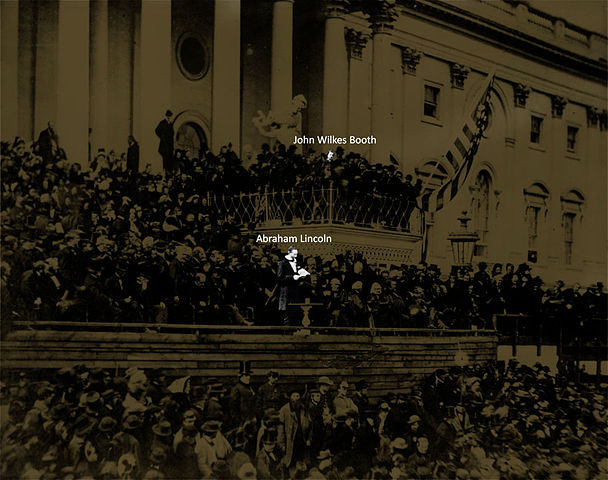

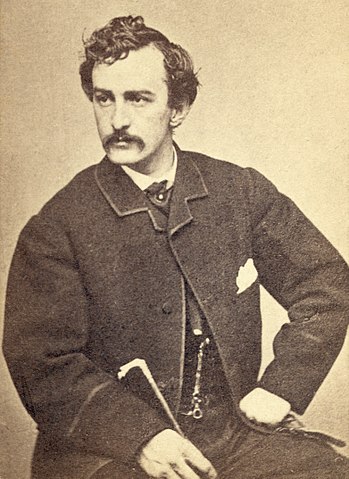

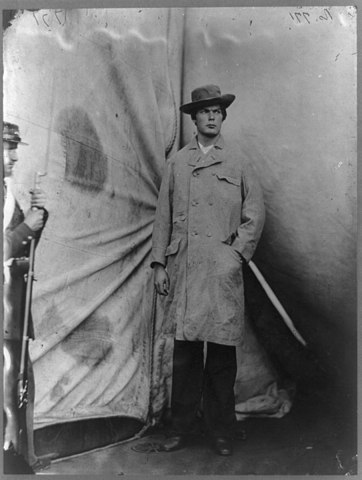

A popular actor, John Wilkes Booth used his professional access to Ford’s Theater to assassinate President Lincoln.

In April of 1865, Booth was an American celebrity. Having earned as much as 20,000 dollars a year, the equivalent of over 600, 000 dollars today, Booth was also described as the handsomest man in America and discretely involved with Lucy Hale, the daughter of a US Senator. But Booth was also a Confederate sympathizer and a virulent racist who was enraged by Lee’s surrender and negatively obsessed with Abraham Lincoln, especially after the President stated that black Union soldiers should be granted the right to vote.

Junius Booth provided his family a rural log cabin home near Bel Air as well as a residence in central Baltimore. Eventually, he constructed a more ornate residence near the log cabin which was called Tudor Hall. It was probably fortunate that John Wilkes was sent to boarding school as a teenager, a development that afforded him distance from his father’s glum and occasionally violent personality.

Gripping and turning the doorknob, Booth timed his entrance perfectly, the entire audience focused on a highpoint of the play. Following this access, Booth reached into the deep right pocket of his jacket, retrieved his derringer and cocked the hammer.

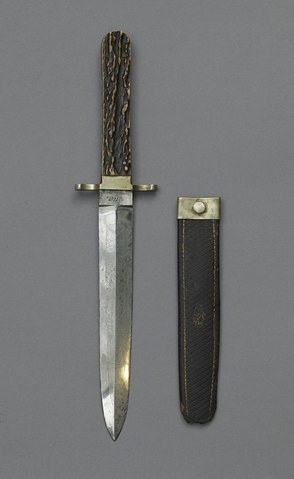

The box was briefly illuminated by the flash of the gun’s muzzle, the .44 caliber round entering the President’s skull, at a diagonal which began at the lower left of the head, below the ear and, travelling upward, lodging behind the right eye. Abraham Lincoln slumped forward, his chin resting on his chest as if he had fallen asleep. For a split second the entire theater sat silently motionless and confused. Only Major Henry Rathbone moved towards the wild eyed intruder who had invaded the box. Booth raised his knife, fully intent on stabbing Rathbone to death but the Major was able to parry the assassin’s downward thrust with his arm, incurring a deep wound near the elbow.

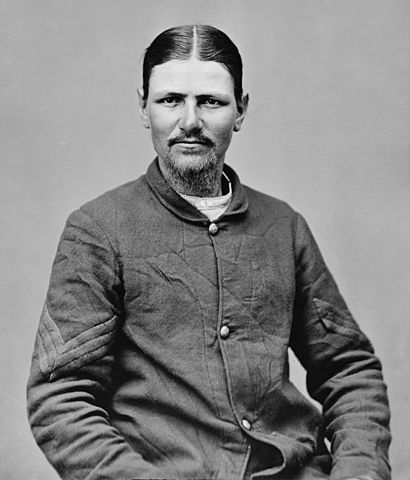

Of his three co-conspirators, Herold was the most valuable to Booth at this point of his flight. The 22 year old was an experienced outdoorsman and hunter who knew this area of the Maryland landscape, even in the darkness. Although jubilant about his attack, Booth’s broken leg was starting to cause him great difficulty. When the pair reached Surrattville, it was Herold who pounded on the door to wake up the already sleeping proprietor of the tavern, John Lloyd. Lloyd retrieved the two rifles and field glasses most likely mentioned by Mrs. Suratt earlier that evening, but Booth took only the field glasses, his injury wouldn’t allow him to hoist a gun. Herold got a bottle of whiskey as well and he and Booth took some generous swallows before paying the innkeeper a dollar as well as regaling him with the stunning news that they had killed the President and Secretary of State. Lloyd was terrified and reacted by beseeching both men to leave as quickly as possible.

About a mile away on Madison Place, the home of Secretary of State William Seward was also the scene of terrible carnage. Seward was already convalescing from the effects of an April 9 carriage accident that broke his arm and jaw. Lewis Powell would use these injuries to gain entrance to Seward’s brick mansion. David Herold, a pharmacist assistant by trade, helped concoct a small butcher paper package tied with string that Powell would claim was medicine prescribed by Seward’s doctor. Powell and Herold waited until the rooms of the mansion were darkened and the occupants were heading for bed. As Herold looked on, Lewis Powell handed him his horse and made his way to Seward’s front door. A black, nineteen year old servant named William Bell answered the knock. In front of him stood a well dressed man with a small package. Powell claimed he had medicine for Seward and even knew the proper name of the physician. Bell accepted this explanation but became adamant that Powell would have to leave the medicine with him. Powell ignored him, pushed his way inside and began to ascend the stairway to the second floor. At the top of the stairs stood Frederick Seaward, son of the Secretary, who also requested that Powell give him the medicine as the Secretary was asleep and could not be disturbed. Powell again insisted that the medicine must be delivered personally. Unbeknownst to Powell, Seward’s bedroom was only a few feet away. At this critical moment, Seaward’s daughter, Fanny, who was bedside attending her father, opened the bedroom door and told her brother that actually her father was awake. Now Powell knew exactly where his prey was but rather than aggressively barging his way in, he continued to argue with Fred Seward who insisted he either leave the medicine or go back to the doctor. Powell seemed to acquiesce but in the split second of walking down the stairs and satisfying Seward’s son that he was leaving, he quickly whirled, drawing a pistol from his coat pocket. Pointing it directly at Seward’s face, he pulled the trigger for what should have been a fatal gunshot. The gun misfired with an ominous click, but Powell began to pistol whip the smaller man into submission while William Bell ran down the stairs and out into the street shouting “murder” at the top of his lungs. After beating Fred Seward half to death, Lewis Powell tossed him aside and turned his attention to his father’s bedroom door.

Booth sensed that his leg needed immediate medical attention, especially if he was to successfully escape. He thought of Dr. Samuel Mudd, but knew Mudd lived in a rural area that is isolated even today, near the small town of Bryantown, MD. Seventeen miles from Surrattville, it took fours hours to get to their destination, and without Herold, Booth never would have found the narrow path that lead to the doctor’s two story, bright white home. At four in the morning, Herold began to pound on another door that Dr. Mudd warily and eventually answered. Booth hung back just as wary as Mudd. Herold explained that there had been a riding accident on the way to Washington and his companion had broken his leg. Mudd recognized Booth as he emerged from the shadows and helped him up the stairs.

Following his Boston performances, Booth then refused any additional work, appearing on November 25, 1864 in New York with his two brothers in Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” Booth promised to participate in this benefit celebrating 300 years of the author’s birth, proceeds to be donated to construct a statue of the Bard in Central Park, which still stands.

One of the first senior government officials to arrive on the scene at the Peterson House was Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Stanton had already been to the Seward home after being informed of the attack by a messenger as he prepared for bed. Eventually hearing about the President, Stanton resolved to go to the vicinity of Ford’s Theater and take charge of the situation as quickly as possible.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS