On February 3, 1959, Buddy Holly was in the middle of the tour from hell and would do anything to avoid another three hundred mile, overnight bus ride that already had inflicted frostbite on another band member. That determination changed American popular music forever.

Charles Hardin Holley was born in Lubbock, Texas on September 7, 1936. The “e” in his surname would be dropped when Decca Records misspelled Holley on one of his first recording contracts. Nicknamed Buddy by his mother, as she considered “Charles,” too formal, he was the youngest of four siblings. The family was Baptist and deeply religious, attending church routinely but singing hymns from an early age probably developed Buddy’s interest in music. Despite Lubbock’s location in the heart of the bible belt, Holly was also intrigued by country and rhythm and blues popular tunes that were available via radio stations from larger midwestern radio stations. By the seventh grade, he was playing with another junior high school student, Bob Montgomery, in a duet called Buddy and Bob, mostly country music covers of artists like Hank Williams.

1957 began with Buddy getting a predictable release from his Decca contract. If you were out of Lubbock, Texas in 1957 and had just been dropped from a major label there wasn’t much of a Plan B. The best Buddy could come up with was heading to Clovis, New Mexico and the Norman Petty Studio to pay for his own demo and hope to interest a regional industry professional, in this case Norman Petty, in getting interested in representing Holly. Norman Petty was one of the many small time independents that operated on the fringes of 1950’s rock and roll. Less successful than the legendary Sam Phillips of Memphis’ Sun records who discovered Elvis, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis, Petty still had a reputation for recognizing performers that he plugged either to record companies or radio stations. But in early 1957, he also was still looking to get involved with talent that would translate into national success. That’s why, when Buddy Holly returned to Petty’s studio in January of 1957 and cut a demo, Norman recognized that Holly had greatly evolved. He told Buddy to get some more material together, polish it up and come back in February and they would seriously concentrate on developing a single, exactly the result Holly was looking for.

When he returned to Clovis on February 24, Buddy not only had three other backing musicians, Larry Welborn, Jerry Allison and Niki Sullivan, he also had Gary and Ramona Tollett as backup singers. Because Petty’s studio was close to a busy street with daytime noisy truck traffic, recording didn’t begin until after office hours. Petty wanted, “I’m Looking For someone To Love,” to be the “A” side of a single and when that was arduously completed over many hours, at 3 AM, it then took only four takes to record, “That’ll Be The Day.” Subsequently, Norman Petty claimed to have greatly influenced this session, Gary Tollett maintained that Buddy already had the arrangements down and all Petty did was arrange the microphones. Nevertheless, Petty then executed two of the more audacious moves in the history of Rock and Roll skullduggery. The first revolved around songwriting and publishing credits. Petty maintained that because he had provided the free use of his studio, had music connections in NY and was a known quantity in the business, his name should appear on the record as one of the songwriters. A known quantity, he explained, is better than some unknown kids from West Texas. He also offered to publish the music through his own Nor Va Jak publishing company, spinning this as a kind of business benefit, explaining that they wouldn’t have to worry about a thing. He didn’t emphasize that this would entitle him to fifty per cent of the publishing revenues, only that this was how the business worked. Buddy Holly was so thrilled that anyone would try to help him get somewhere that he didn’t give it a second thought.

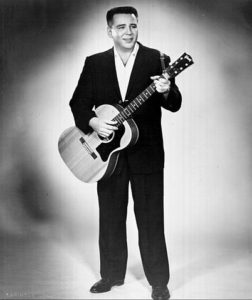

No Hollywood screenwriter would have attempted to put over the story of Valen’s overnight success at such a young age. When a well connected LA music producer named Bob Keene got a tip that a precocious sixteen year old phenom was performing at a movie theater in the Valley, he decided to check out the youngster performing as Ritchie Valenzuela. The teenager already had a following as the “Little Richard of the Valley,” and Keene signed him to a contract right away, promising to both help record and manage Ritchie’s career. After rehearsing Ritchie in the basement studio of his Silver Lake home, in June of 1958, Keane booked a session at Gold Star Studios, to put together a single. From this emerged Ritchie’s first song, Come on, Let’s Go!” Keane was involved in producing Sam Cooke’s first hit, “You Send Me,” and although he was financially outmaneuvered by his then business partner, Keane was an astute industry professional. He convinced Ritchie to change his professional name to Valens explaining that DJ’s wouldn’t play an obviously Latino artist on commercial pop radio. He then met with the music director of KFWB, a personal friend, who made playlist decisions for the biggest radio station in Los Angeles. Keene’s contact did not need much persuasion, within days of Ritchie’s first recording session, Come On, Let’s go was in the rotation at most Southern California radio stations. It gradually become a nationally popular song and Keane, wanting to put together enough material to allow Ritchie to headline on tour, quickly rushed Valens back into the studio. Having spent time driving the singer to various local shows in SoCal, Keane had heard Ritchie singing a Mexican folk song to himself on acoustic guitar, called La Bamba. Ritchie’s manager was intent on doing something with the song, but Valens did not like the idea of exploiting a traditional Mexican folk tune in a rock and roll song. Instead, in a repetition of how “Peggy Sue,” originated, Ritchie was intent on recording, “Donna,” a song about a high school classmate. Donna Ludwig was an Anglo 16 teen year old whose father would not have approved of even a fifties teen age romance with a Latino. She frequently took to climbing out of her bedroom window to meet Ritchie at local soda fountains and roller rinks. In the studio, Keane compromised. Ritchie would record both songs as A-Sides, giving him two shots at a potential hit. By November Donna was steadily rising up the charts, it would be at #3 in early February of 1959. By the time Ritchie Valens hit Chicago, he had dropped out of high school, bought his mother a house and was on the verge of banking over $100,000, heady stuff for a seventeen year old whose extended family previously subsisted on picking asparagus and plums in the yet undeveloped farmlands north of Los Angeles.

Holly was business savvy enough to remember and understand that his previous deal with Decca forbade him for five years to use any of the songs recorded during his tenure there. That included, “That’ll be the Day.” Petty’s second utterly brazen move to get around this was to suggest recording this with the name, as yet still undetermined, of a band. A couple of days later, because of their familiarity with another group known as the Spiders, Holly and Jerry Allison started to consider other insect names, actually considering the Beetles with a double EE before settling on the Crickets.

JP Richardson, aka the Big Bopper, known chiefly for his top 40 novelty hit of the previous September, Chantilly Lace. Richardson drew from his previous employment as a disc jockey, weaving comic dialog into an irrepressible melody while wearing a full length dyed leopard skin fur coat and white bucks, undoubtedly giving himself an interesting stage presence.

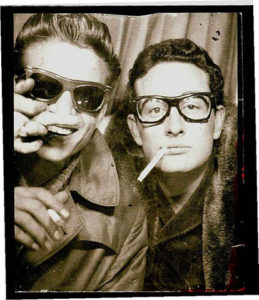

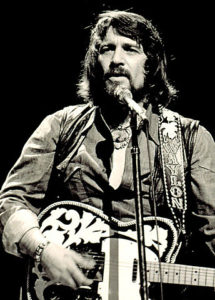

To fill out his backing band for the Winter Dance Party, Buddy convinced a Lubbock DJ and musician named Waylon Jennings to join as the bass player, despite Jennings having no bass experience. Buddy hung out a lot at the DJ’s station, WLLL the most popular in Lubbock and liked Jennings, he told Waylon he would buy him a bass and teach him everything he would need to know before the tour started.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS