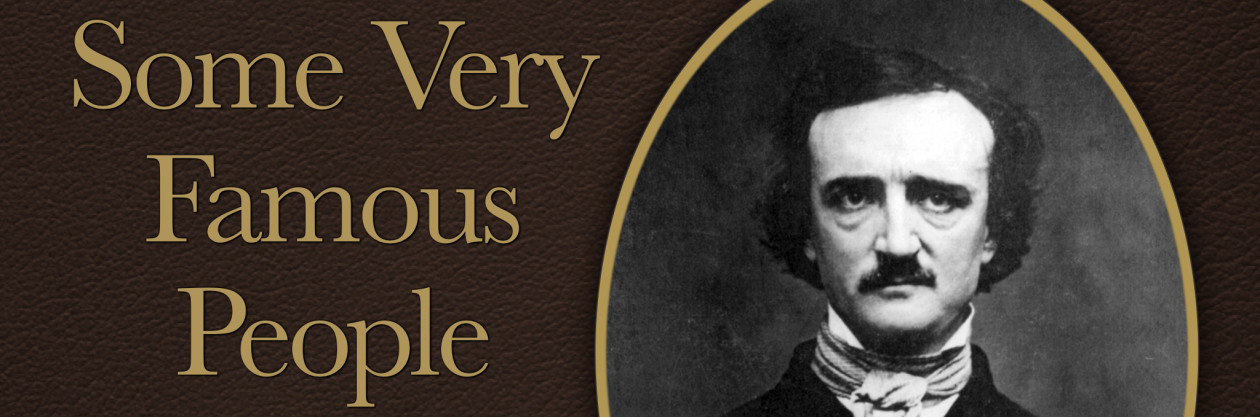

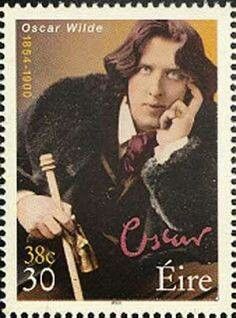

In March of 1895, Oscar Wilde enjoyed fame and fortune as one of Britain’s foremost literary figures. Only four months later he was inprisoned for the crime of “gross indecency,” convicted of violating Britain’s laws against same sex relationships. Upon his release, he exiled himself to France, his career in ruins and never saw his family again.

At Oxford, Wilde continued his immersion in the classics. The school was definitely a step up in class, his fellow students having matriculated at Eton, Harrow or similarly upper class English preparatory environments. Many were also comparatively much wealthier than the modestly affluent Irish native. A later journalistic account described him as initially, naïve, embarrassed, with a convulsive laugh, a lisp and Irish accent.

Wilde sailed for America, arriving in New York on January 2, 1882. Oscar, who received a great deal of attention in London’s society columns, and whose tour was widely publicized in both Britain and the US, was swamped by journalists, even before he was able to clear customs and disembark, the press actually hiring boats to interview Wilde offshore.

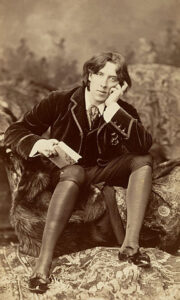

Wishing to represent himself as an aesthete in appearance as well as philosophical perspective, Wilde greeted the press in a full length green topcoat, trimmed with fur on the cuffs and collars, a similarly colored and trimmed rounded green hat on his head, hair much longer then was typical. A large collared shirt with light blue tie was visible underneath this outer layer. He also wore a large seal ring with a classical Greek profile.

Oscar Wilde also remained focused on Constance Lloyd. In Dublin, for a series of lectures, he was invited to the home of relative’s of Constance’s mother, Adelaide Atkinson Lloyd. There, Oscar and Constance spent time together and socialized for the next few days, Constance attending both of Wilde’s Dublin lectures. On November 25, the couple were left alone in the drawing room of the Atkinson home, the same room where Constance’s father proposed to her mother. Here, also Oscar Wilde proposed to Constance Lloyd. She accepted immediately and was described as, “insanely happy.”

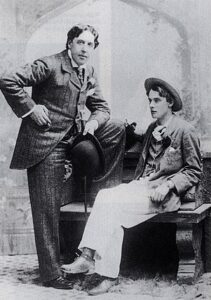

But just as Wilde reached the heights of public popularity, his private life resulted in his complete personal ruin and professional destruction. Although his vow of celibacy applied to his relationship with his wife, it did not preclude Wilde from consorting sexually with men, on a frequent basis that included what were termed, “rent boys,” young, working class males typically in their late teens. Wilde was also emotionally involved with Lord Alfred Douglas, nicknamed Bosie, a student at Oxford when Wilde was introduced to him. The two began a tempestuous lengthy relationship that was also quite indiscrete.

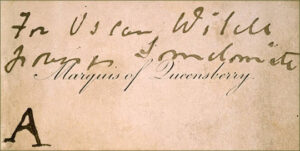

On February 28, 1895, Wilde entered a private club of which he was a member, the Albemarle Club. He was hailed by the doorman, who handed him an envelope, stating that the enclosed card was dropped off ten days earlier. Inside was a card embossed with the Marquess of Queensbury’s name and written in script, “For Oscar Wilde- posing Somdomite,” the last word misspelled but written with clear intent. Only the card was delivered, it was judiciously placed in an envelope by the doorman and could have easily been seen by staff, as well as members, which included women.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS