Harriet Tubman, righteous heroine

Harriet Tubman was born Araminta Ross in the eastern shore region of Maryland in 1822. Her exact date of birth remains unknown. Both of her parents were slaves, Harriet (Rit) Green and Ben Ross.

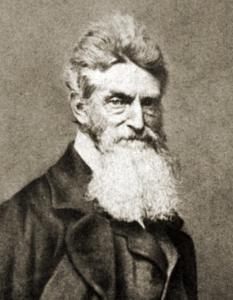

The summer of 1859 also brought a resumption of John Brown’s plan for rebellion. He was already gathering assets in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in anticipation of his planned attack on the Federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to seize the arsenal and armory, incite local slaves to join his rebellion and spread a slave revolt as effectively as possible. Brown was fanatically opposed to slavery with an opposition rooted in a deep religious fervor. He considered himself a divine instrument intent on imposing punishment on those conducting the sinful practice of slavery. Based on his interaction with Harriet Tubman, Brown fully expected her to join his effort. He repeatedly attempted to contact her to no avail but he did meet with Frederick Douglass in Chambersburg. When Douglass realized that Brown was intent on attacking a federal arsenal he told him that “he was going into a perfect steel trap, once in, he would not get out alive.”

Harriet Tubman also aided in the celebrated 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment in its participation in the attack on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor on July 19, 1863. The 54th was one of the first African-American regiments assembled during the Civil War. Commanded by a white abolitionist, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th was in the vanguard of the assault on Fort Wagner, a heavily fortified beachhead that was part of the defensive infrastructure protecting the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. After a lengthy bombardment, the Regiment began a frontal assault on the fort. Despite heavy losses, the 54th was able to briefly seize part of the south wall but heavy hand-to-hand combat and artillery fire pushed the unit back. Other Union regiments also attempted to breach the fort around its perimeter but were repulsed with terrible losses. An estimated 1,500 hundred Union troops were killed, wounded or captured. The 54th lost over two hundred and fifty men. Robert Gould Shaw was killed in the initial storming of the fort and buried in a common grave with his fellow black soldiers. While the grave was eventually washed away by storms and the remains of these soldiers disappeared, the heroic story of Gould Shaw and his men has been immortalized in the film “Glory.”

Five days after the armistice at Appomattox, President Lincoln was assassinated and Harriet’s benefactor Secretary of State William Seward was incapacitated by an assailant involved in the same plot. Although Seward would survive and even attempt to help Tubman in her attempts to receive back pay, she eventually decided to head back to her home in Auburn, NY.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS