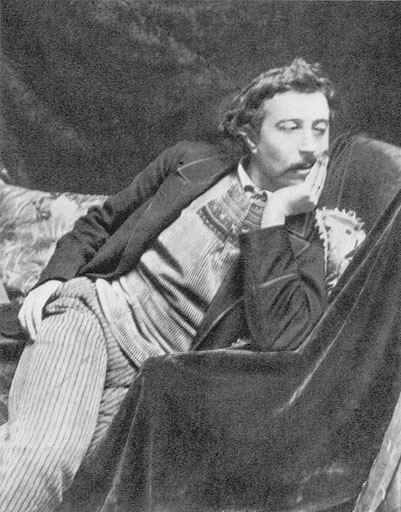

Paul Gauguin, the Bitterness and the Beauty

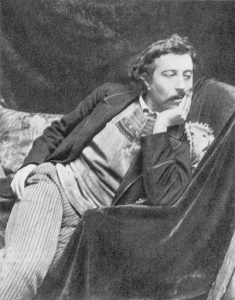

From his very first days, Gauguin’s life was filled with a volatile instability that must have affected his development. He was born in Paris on June 7, 1848. His father, Clovis, was a journalist, his mother, Aline, the daughter of Flora Tristan, a seminal feminist writer of the early nineteenth century. Aline’s father had been imprisoned for the attempted murder of Flora, an indication of the chaos surrounding Gauguin’s immediate family. Flora Tristan died in 1844, and in 1847 Aline married Clovis and soon settled down to married life and the birth of a daughter in 1847 and Paul in 1848. But the political unrest of Paris forced the young family to think about heading into exile.

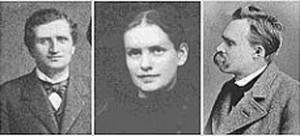

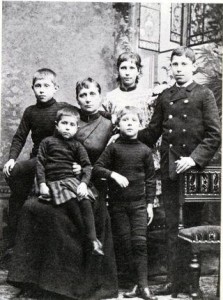

It was at the home of Gustave Arosa that Gauguin, in November of 1872, met two female guests, travelling from Denmark. One of these woman, Mette-Sophie Gad, was immediately attracted to Gauguin and a yearlong courtship began. Mette was no great beauty, but all accounts indicate that she had a great deal of personality and a practically masculine outlook that could handle the rough edges of an ex-sailor. A year later the couple would be married and Mette would rapidly become pregnant, Paul’s stock market employment providing a comfortable lifestyle.

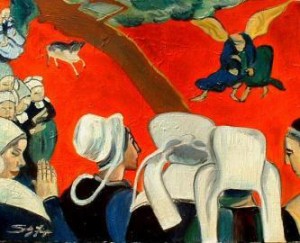

With the death of Theo Van Gogh and the realization that none of his compatriots would leave France for the exotic destinations that he continually fantasized about, Gauguin became fixated on a newer and even more remote destination: Tahiti. Again he held out for a major sale and a large check that would get him out of France. He had maintained this fantasy for decades but this time his growing reputation and a newspaper article published the day before a planned sale at the prestigious auction house at the Hotel Druout insured that his paintings would generate a substantial sum. In all thirty paintings were sold on February 23, 1891, including “Vision After the Sermon” and the portrait “Beautiful Angela” which was purchased by Degas.

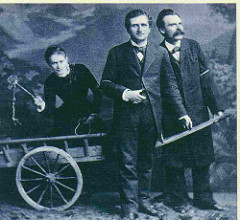

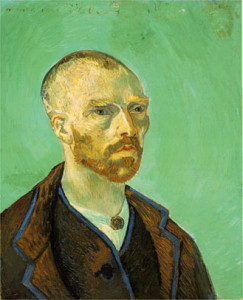

Vincent Van Gogh had spent the summer writing to all of the artists of Pont-Aven, imploring them to participate in a “colony” in Arles, where he had already relocated. Gauguin repeatedly put him off by claiming that he would have to wait until he sold some paintings and raised the money to pay off his debts in Brittany. But when Theo Van Gogh sent him some money and promised more if he would merely agree to join Vincent in the south of France, Gauguin acquiesced. The overjoyed artist sent him a remarkable, jade green self portrait dedicated to “mon ami Paul” and typically began to fixate on when Gauguin would arrive or if he would even show up at all. Thus the stage was set for one of the most notoriously tragic incidents in art history.

A sequence of events in late December brought about Gauguin’s inevitable departure. As the weather kept them painting indoors, Van Gogh returned to his familiar motif of sunflowers, Gauguin painted a portrait of Vincent at work. The result horrified and angered Van Gogh. “It is certainly I, but it’s I gone mad!” That night at a cafe an argument culminated in Van Gogh throwing a glass of absinthe at Gauguin, who dragged him home and put him to bed. Although Van Gogh tried to apologize, Gauguin responded by saying he could no longer stay because he might respond to such future outbursts by strangling Vincent.

A terrible rainy season insured that Gauguin and Van Gogh would spend most of their time shut up in the Yellow House, unable to paint outside. They spent much of their time in philosophical discussions that ultimately became hostile, Gauguin condescendingly dismissive towards all of Van Gogh’s opinions especially when it came to art.

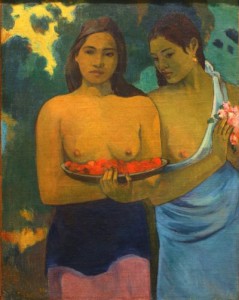

Gauguin’s deteriorating health affected his productivity but he still would produce some of his greatest works during this time period, especially, “Two Tahitian Women”, now in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

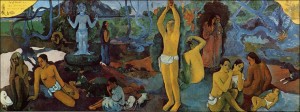

He also produced the allegorical “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? that is now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS