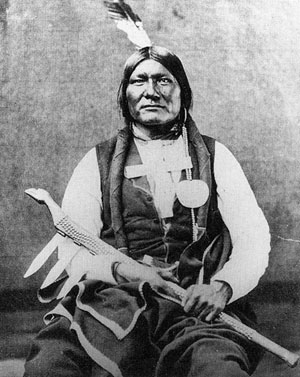

Most likely, Crazy Horse was born in the spring of 1840, in the Black Hills of western South Dakota, near Rapid City. His father was a member of the Oglala clan, also named Crazy Horse, and his mother, Rattle Blanket Woman was a Minniconju.

The Lakotas and Cheyenne were generally aware of the federal presence but believed that only a fool would attempt to attack such a large and powerful position. But, at 3 PM, attack Custer did, ordering 140 cavalry on horseback under the command of Major Marcus Reno to engage the south side of the giant native village on the western shoreline of the Little Bighorn River. Custer planned to take his command of 200 men and proceed along the river, ultimately leading an attack upon the northern side of the village.

Custer’s strategy, relying on his own success at the Washita and other battlefield experience, was simple. He divided his 12 companies into three units. Three companies commanded by Major Marcus Reno would attack the encampment from the South, Three would be commanded by Captain Frederick Benteen, held in reserve to pursue any subsequent advantage and five units would be lead by Custer himself, attacking the village from the North. One unit would be held behind to customarily protect the regiment wagon train of material and ammunition.

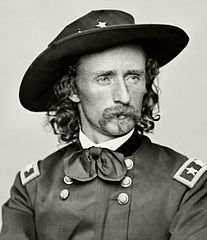

Although weakened and disorganized, Crazy Horse and other non-treaty natives were adamant that they would not move on to a reservation. Perhaps as a further attempt to intimidate them, in 1874, Phil Sheridan ordered General Custer to march directly into the Black Hills with a force of over one thousand well-equipped soldiers. Accompanying the expedition were mining engineers who quickly determined that the entire region was replete with sizable gold deposits. Custer, a shameless self promoter, also travelled with several journalists who wasted no time in informing an economically challenged American population that gold was everywhere in the Black Hills.

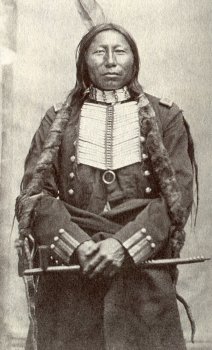

Unlike previous incidents, this time there was some warning of an attack and as Reno approached, numerous warriors on foot and on horseback rapidly emerged to bring this assault to an immediate halt. The cavalry was quickly forced to dismount and set up a battle line that hastily became defensive. Several Lakota chiefs, including He Dog and Brave Heart were soon involved in the fight but as the conflict escalated, one notable combatant remained absent. The most respected and prominent Oglala warrior, Crazy Horse, was swimming in the river when the fighting started.

Custer’s initial strategy involved an attack on the northern edge of the encampment, splitting his companies into two units, commanded by Myles Keough and George Yates, with Custer retaining overall command. This dual assault followed natural ravines in an attempted crossing of the Little Bighorn. But Custer quickly ran into the same predicament as Reno. He also ran into Crazy Horse as well as another native column lead by the Hunkpapa warrior chief Crow King. By 4:35, Crazy Horse had traversed the two miles from the vicinity of the Reno skirmish and was now organizing a response to Custer’s aggression. The Hunkpapa and Cheyenne contingent would confront the Yates column and quickly drive it backwards in retreat while Crazy Horse lead a one and a half mile ride of the Oglalas which forded the Little bighorn river at a spot known as Deep Ravine and then attacked the Custer-Keough battalion on its right rear flank. Both battalions would eventually retreat to a spot known as Calhoun Hill. They would be surrounded by the two separate native columns, Crazy Horse leading a looping encircling movement from the Northwest, Crow King pressing the attack from the South.

Although Custer’s command is traditionally believed to have been wiped out on high ground now known as Custer Hill, how and exactly where the US detachment and Custer met their end is still a subject of academic debate. Native descriptions indicate that the entire secondary battle took little more than an hour and the last surviving troops were overwhelmed by a final charge of warriors, the conflict now a desperate hand- to-hand struggle in which soldiers had no time to reload, and natives relied on war clubs and hatchets to attack and then kill. Modern analysis indicates a final breakout attempt of two-dozen men who were trapped in a nearby canyon and then finished off. Several warriors claimed credit for killing Custer but as one native participant eventually stated: “If we could have seen where each bullet landed, we might have known. But hundreds of bullets were flying that day.”

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS