In 1770, the French people greeted Austrian Marie Antoinette as the beautiful and future French queen. Twenty-three years later they guillotined her as the most reviled woman in France.

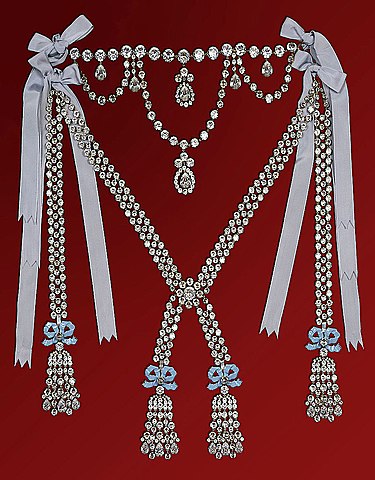

The affair of the Diamond Necklace had its origin in a piece of jewelry that was commissioned by Louis XV in 1772 and meant as a gift for his mistress, the Madame Du Barry. He requested that the royal jewelers Charles Boehmer and Paul Bassenge create a diamond necklace that exceeded anything previously produced. On spec, the two men took great pains to assemble a creation that incorporated a great number of exquisite diamonds in a staggeringly large and ornate necklace. Called, “The Slave’s Collar,” and consisting of over 2800 carats of diamonds, the worth of this necklace today has been estimated to be as high as one hundred million dollars. Unfortunately, the King died before this accoutrement could be finalized, the jewelers now stuck with a very expensive piece of jewelry and an extremely small pool of potential buyers, the most obvious Louis XVI. But twice, in 1778 and again in 1781, for one reason or another both the King and Marie Antoinette declined to purchase the necklace. Unsold, this became the basis of an elaborate confidence scheme hatched by a socially and financially ambitious woman who called herself the Comtesse Jeanne de la Motte.

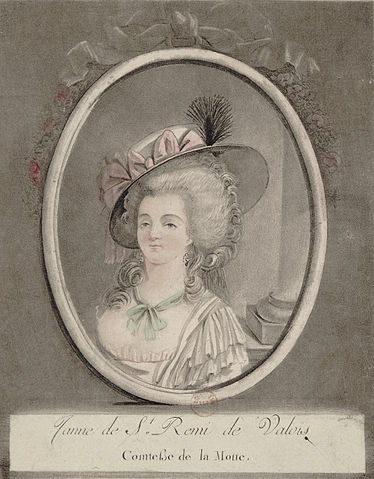

By late 1784, Jeanne had ingratiated herself as the mistress of the Cardinal de Rohan, not only a member of the powerful de Rohan noble family but a former diplomat deployed in Vienna to the court of Maria Theresa. Unfortunately, his dissolute lifestyle and anti-Austrian bias earned him the antagonism of the Empress, who in turn delivered her opinion of the Cardinal to Marie Antoinette. Upon Louis XVI assuming the throne, De Rohan, most likely upon the urging of the Queen, was hastily recalled. Understanding that the Cardinal was desperate to improve his status within the French court, Jeanne de La Motte convinced De Rohan that she was well connected to especially Marie Antoinette. In fact, through a forger, fellow huckster and also feigned aristocrat Armand Retaux de Villette, Jeanne was able to access the French Court. She further convinced de Rohan that the Queen had officially acknowledged her and that Marie Antoinette held her in high esteem. De Rohan then began what he thought was a correspondence with the Queen, receiving letters in return that were actually forged by Retaux de Villette. Blinded by his ambition, De Rohan did not hesitate when Jeanne began asking for loans and even produced signed letters which requested that he help the Queen secretly acquire the, “Slave’s Collar,” to avoid public and even Louis XVI’s awareness of such an exorbitant purchase, an acquisition that might inflame hostility over royal expenditures even further. To add further credibility to the scheme, De La Motte and Retaux de Villette staged a nocturnal, secret liaison between the Cardinal and a woman he thought was Marie Antoinette. In fact, the two confederates hired a prostitute who resembled the queen, Nicole d’Oliva, the three arranging to meet the Cardinal in a remote corner of the gardens of Versailles. In the darkness, d’Oliva, dressed fashionably, approached the Cardinal, handed him a rose and breathlessly intoned, “You know what this means, the past will be forgotten” before quickly and stealthily retreating.

Convinced that he was on the verge of a great political restoration and even deluded enough to believe that Marie Antoinette was physically attracted to him, De Rohan now reached out to the jewelers, who were also blinded by their zeal to unload the necklace. With, unbeknownst to him, forged letters in hand from the purported Marie Antoinette, requesting that the Cardinal act as her representative, a deal was negotiated whereby the necklace would be paid for in installments. Of course, the transaction was to occur amidst the utmost secrecy, a condition De La Motte could not emphasize enough. The necklace was secured by the Bishop, he then was instructed to turn it over to an individual described as a valet of the Queen, in fact Nicholas de la Motte, who hastily fled to London. By the time the alleged count arrived in England, the diamonds had been pried out of their settings, many damaged during the process, but still able to be fenced.

Marie Antoinette’s son and heir, the dauphin Louis Charles, already considered by royalist emigres as the de facto Louis XVII, was treated just as brutally. After his mother’s execution, he was placed in a solitary, damp cell, fed through the bars, with little interaction with his jailers. He endured such conditions for sixth months, until a change in government allowed for the improvement of his confinement. By then he had contracted tuberculosis, the ailment which killed him on June 8, 1795, aged ten years old.

Louis XVI’s brother, the Comte de Provence was crowned Louis XVIII after Napoleon’s exile to Elba. His reign interrupted by the one hundred days and Waterloo, he ruled until 1824.

Louis XVI’s youngest brother as Charles X, a ruler so odious and reactionary that he prompted a second popular revolution, an event that caused his abdication.

Back at the Temple, Marie Antoinette was not formally told of her husband’s death but the noise and tumult from the street down below told her and her family everything they needed to know. From that day on, she received and wore black mourning clothes and descended into a hopeless depression.

On July 3rd, Marie’s status took an ominous turn when she was informed by her jailers that she was to be separated from her son. Additional Austrian victories now placed Paris in even greater danger. As a result, at two o’clock in the morning on August 2, Marie Antoinette was transferred to the Conciergerie, a much more secure and foreboding courthouse and prison. There was no attempt to spruce up her new environment or disguise its intent, the damp brick, bed, rudimentary chair and bucket toilet of a prison cell. A hapless attempt by royal sympathizers within the prison known as the Carnation plot only served to tighten the security around Marie Antoinette. From then on armed sentries remained in her cell, subdivided with a simple wooden screen which did little to protect Marie’s modesty.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS