In March of 1895, Oscar Wilde enjoyed fame and fortune as one of Britain’s foremost literary figures. Only four months later he was inprisoned for the crime of “gross indecency,” convicted of violating Britain’s laws against same sex relationships. Upon his release, he exiled himself to France, his career in ruins and never saw his family again.

Unfortunately, their reunion was so successful that both men began contemplating running off to Naples, the consequences be damned. Robert Ross and various other associates and friends of Wilde soon heard about this development and were all uniformly dismayed. Wilde was literally living off his wife’s allowance, funds that would be jeopardized if the news of his rekindled relationship with Bosie became known to her and especially her attorneys. Even so, he needed to borrow money just to get to Naples by train, leaving this important fact out of any discussions he had about his reasons for heading to Italy.

Robert Ross’ belief that Wilde’s literary reputation would eventually be reconstituted occurred faster than even he anticipated. By the beginning of the 20th century, various critical analyses and biographies and accounts of Wilde’s life appeared to great interest. His plays never really disappeared for any length of time, their popularity in British regional theater continued and all of Wilde’s theatrical works returned to popularity internationally as the century progressed. By 1908, Ross had successfully repurchased all of Wilde’s copyrights that were sold off during Oscar’s bankruptcy proceedings. These rights were then returned to Wilde’s sons.

John Sholto Douglas, the ninth Marquess of Queensberry. Aggressively masculine and a sportsman, as opposed to his sons, the elder Douglas, is credited with creating what are known as boxing’s “Queensberry Rules,” the ten basic rules that govern boxing even today. Despite great wealth, Douglas was extremely hostile, and possibly mentally ill.

Although his wife also restored a modest allowance of ten pounds a month upon hearing of his break with Douglas, Wilde received the news that she died on April 7, 1898 after a botched operation to relieve her paralysis. She was buried in Genoa, her gravestone using her newly assumed name of Holland with no mention of Oscar Wilde.

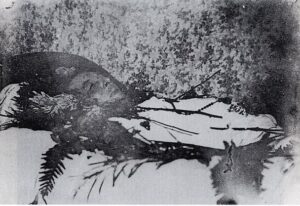

Finding Wilde borderline delirious and hearing that he had no more than days to live, Ross then went to the nearest Catholic church and brought back an Irish priest who quickly went through the official ceremony of converting Wilde to Catholicism. Ross also sent cables to Frank Harris and Alfred Douglas, warning them of Wilde’s current state. By the morning of November of November 30, Wilde had lost consciousness and was completely unresponsive. He died that afternoon.

Ross also transferred Wilde’s remains from Bagneaux to the more prestigious Parisian cemetery at Pere Lachaise, already the resting place of Chopin, Balzac, Moliere and eventually Sarah Bernhardt, Edith Piaf and Jim Morrison. Ross also collected funds for a magnificent sculpted abstract sphinxlike creature, requesting that the artist Jacob Epstein include a compartment for the internment of Ross’ own ashes, a request that was not fulfilled until 1950, 32 years after Ross’ death at age 49 of a heart attack. Epstein’s monument is perhaps too magnificent, it was repeatedly vandalized by lipstick kisses until cemetery authorities cleaned it and installed plexiglass to prevent such future vandalism.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS