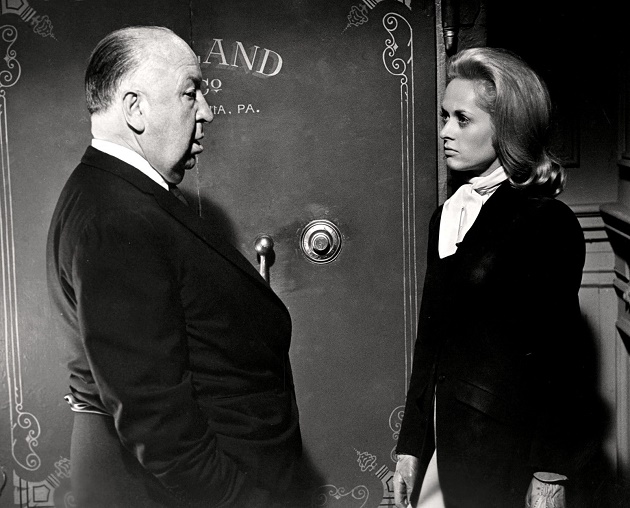

In his sixty year career, Alfred Hitchcock established himself as one of the most important cultural figures of the 20th century

Hitchcock broke into show business by getting a job with the newly arrived motion picture studio Famous Players-Lasky British Producers, a venture associated with Paramount Pictures. He was to design the captions that accompanied the action in the studio’s silent films. Initially, a part time employee, Hitchcock worked hard, keeping his day job at Henley’s but eventually landing full time at Famous Players Lasky in 1921.

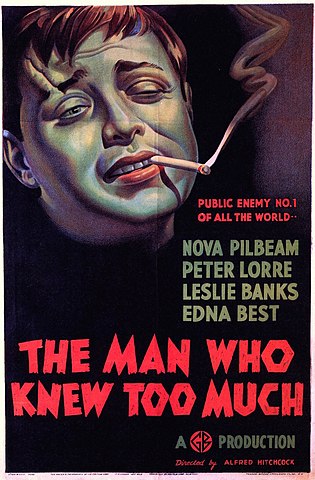

Hitchcock spent the next few years directing and producing various dramas, thrillers and even a musical revue before his 1934 effort, The Man Who Knew Too Much. Possessing the same title as his subsequent 1956 effort with Doris Day and Jimmy Stewart, the film has a similar plot involving kidnapping, political assassination and criminal intrigue. It also cast Peter Lorre, having recently fled Germany after his great success in the Fritz Lang classic, “M.” Lorre, who was Jewish and was uncomfortable with Hitler’s acquisition of political power, barely spoke English and ingratiated himself with the director by anticipating when Hitchcock, already a budding raconteur, would finish a story, laughing noisily despite not understanding a word of the anecdote. For the part, the Hungarian born actor had to learn his lines phonetically. Lorre’s mysteriously interesting face was featured on the film’s poster and “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” was received with great acclaim and popularity, reaffirming Hitchcock as a major figure in British cinema.

Hitchcock was headed to greener pastures in the United States. Sailing on the Queen Mary on March 1, 1939 with his family, his personal secretary, Joan Harrison, two servants and two dogs, he and his wife were eager to leave. They believed that Hitchcock had accomplished everything he could possibly achieve in Britain and Hollywood allowed him much greater opportunity. He could afford his entourage, having signed a five-picture deal with David O. Selznick, with a guaranteed $50,000 salary for his first picture, Rebecca.

One aspect of the production of Rebecca that prevented any permanent damage to Hitchcock’s business relationship with Selznick was the producer’s preoccupation with the lead up to and release of Gone With The Wind. Selznick also anticipated a profitable gambit to make money on his contract with the director without having to immediately produce another picture. He loaned Hitchcock to independent producer Walter Wanger at a fee of $5,000 a week while he only had to pay Hitchcock $2500. A compulsive gambler, methamphetamine addict and profligate spender, Selznick was perpetually strapped for cash. He could also keep the director at arms-length while the two figured out how to work together in the future.

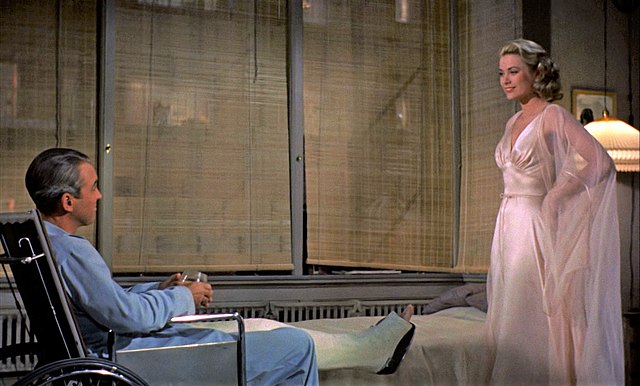

Hitchcock began filming Rear Window in November, 1953, only weeks after completing Dial M for Murder. His enthusiasm combined with his established crew of technical associates handling wardrobe, script supervision, music soundtrack, sound technicians and a stage set so large Hitchcock frequently needed a walkie-talkie to communicate with his cast produced a remarkable effort. Although this was a complex project, it went as smoothly as any Hitchcock production, Hitch even enjoying the practical joke of having Raymond Burr, the film’s villain made up to look exactly like David O. Selznick. Box office was sensational and the critical response transcended the usual Hitchcock accolades.

Robert Walker’s Bruno Antony pushed the limits in a Hitchcock film, strangling his victim onscreen and employing a nasty malevolence unlike any previous Hitchcock character. His borderline personality is underlined by a Hitchcock designed tie embellished with closed-clawed lobsters and a garishly over-the-top smoking jacket that screams twisted among other things. In selecting Walker, Hitchcock made a curious casting choice relative to his former colleague David O Selznick. Walker was deeply upset by the 1943 collapse of his marriage to Jennifer Jones. Jones’ affair with Selznick was the worst kept secret in Hollywood and Jones left Walker while both were performing in a 1943 Selznick produced film. Her subsequent marriage to the much more powerful producer depressed and humiliated Walker. When cast in Strangers On A Train, the actor had spent the previous year in a mental hospital battling alcoholism and a psychiatric disorder. Perhaps Hitchcock sensed that to achieve a realistic portrayal of a an individual with a tenuous grip on sanity, he needed to use someone truly familiar with such mania. Walker’s portrayal of an intensely destructive personality enhances the film’s climax which utilizes an amusement park merry-go-round that goes flying out of control graphically hurling debris into a cloud of onlookers. That Hitchcock accomplished this by blowing up a toy carousel and enlarging the result does not diminish the sense of realistically violent destruction.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS