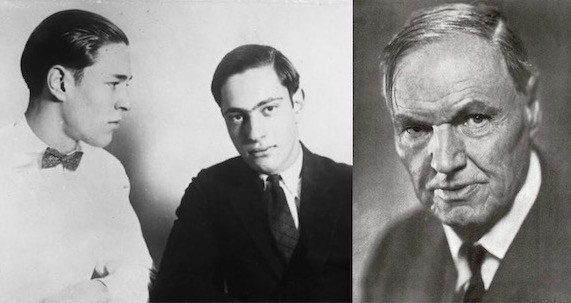

Long before Claus Von Bulow or OJ Simpson, in 1924, two Chicago teenagers committed what was called at the time, “The Crime of the Century,” only to be spared by the efforts of the greatest defense attorney in American history.

Clarence Darrow would not begin his summation until the afternoon of August 23rd, so anticipated throughout the city of Chicago that a mob descended on the courthouse hoping to push into the courtroom. This throng congregated in the stairwells, common areas and hallways leading to the sixth floor chamber where Darrow was scheduled to speak. Twice after the midday recess, the famed attorney attempted to begin his summation, only to stop, the noise of spectators emanating from the hallway outside of the court too boisterous, police and bailiffs struggling to push the crowd out of the courtroom’s proximity. Angrily, the judge contacted the city police chief directly, demanding that order be restored. Within minutes, additional police resorting to billy clubs eventually removed the source of this distraction.

Darrow immediately lived up to his reputation. Although he had formulated his strategy well in advance, he surprised the court, the media, the prosecution and even the defendants after a lengthy opening statement by pleading his clients guilty to both murder and kidnapping. Strategically, this was a brilliant maneuver on several fronts. It ambushed Crowe by not allowing the prosecutor to potentially get two bites of the apple in attempting to condemn the defendants. If he was aware of this strategy in advance, he would withdraw most likely the kidnapping charge and attempt to retry it later. Darrow’s plea circumvented that option. The decision as to what sentence the defendants received now was the sole responsibility of the judge, who would be asked to personally condemn two teenagers as opposed to a jury.

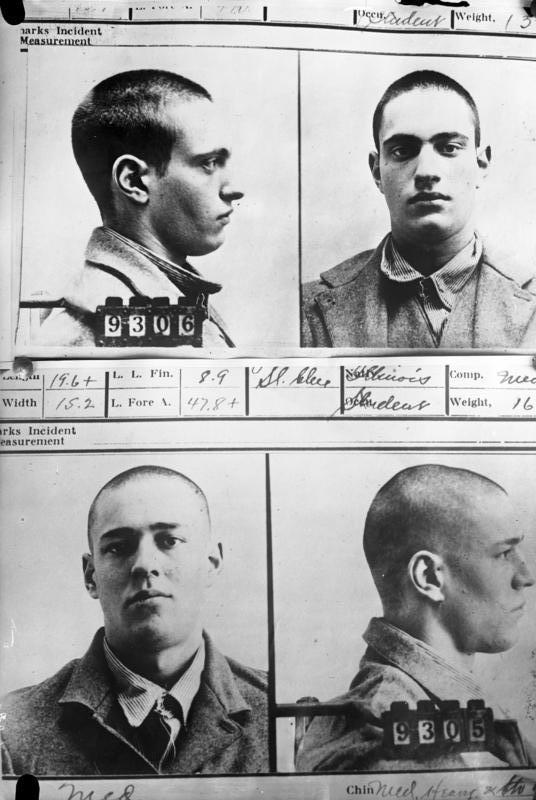

On the eleventh of September, 1924, Leopold and Loeb would begin serving hard time at Joliet state prison, a forbidding stone edifice housing some of Illinois’ most hardened criminals. One immediate hardship was the end of the meals that they were able to order from a Chicago restaurant during their trial. Although they granted interviews upon their entrance to the prison, Loeb would never publicly speak again and Leopold waited twenty years before interacting with a journalist. This despite repeated press attempts to provide updates on the successive anniversaries of their incarceration. Possibly to separate the two prisoners, Leopold was quickly transferred to Stateville prison, a brand new maximum security facility. The formerly high profile prisoners were so isolated that Leopold only found out about the 1929 death of his father from a prison employee.

Despite his recent parole rejection, Leopold cooperated with the Saturday Evening Post on an April, 1955, four part series that was sympathetic. Even more eventful was the 1956 novel Compulsion written by Meyer Levin, a runaway best seller that was a very thinly disguised account of the Loeb and Leopold murder and an eventual film starring Orson Welles. Once again, Nathan Leopold was an American celebrity, although he hated the book and sued Levin and 20th Century Fox for invasion of privacy, an unsuccessful suit that dragged on for most of the rest of his life. Perhaps, attempting to tell his side of the story, in 1958, Leopold published Life Plus 99 Years, a sanitized autobiography also undertaken to persuade any future parole proceedings. A best seller, the book created an additional groundswell for Leopold’s release. This sentiment finally played out on February 13, 1958 when Nathan Leopold emerged from Stateville Prison, a free man.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS