According to the Library of Congress, The Wizard of Oz is the most viewed film in the history of motion pictures.

Most of the other roles were plugged in with various MGM contract players or veteran character actors who got salaries lasting only a few weeks. Ray Bolger was initially asked to play the Tin Man although he had his heart set on the Scarecrow. Buddy Ebsen didn’t really care who he played and his agreement to swap roles with Bolger and play the Tin Man had dire consequences. A second tier actor Bert Lahr, better known for his Broadway comedic ability was cast as the Cowardly Lion.

The dog, Toto, depicted by Denslow seemed a straightforward small terrier but finding such an animal able to function in a soundstage environment amidst the typical commotion, lighting and sound effects became a formidable project in itself. Dozens of visually suitable dogs were auditioned by LeRoy personally, none were even close to what the role technically required. This process grew so unproductive that consideration was even given to dressing up an actor in a dog costume. Finally, a professional dog trainer with previous experience providing animals to the motion picture industry heard about this unique talent search. Carl Spitz was a German immigrant operating a ten acre kennel, dog boarding and training facility in the San Fernando Valley who occasionally padded his income with a movie role for one of his own trained pets. The St. Bernard used in Clark Gable’s 1933 Call of the Wild was to date Spitz’ most famous canine movie star. Upon hearing about MGM’s difficulty in finding just the right animal, Spitz took a gamble on a small female Cairn terrier he owned named Terry. Initially a dog dropped off by a customer for traditional training, Spitz kept the dog when the patron couldn’t afford to pay the bill and never came back to retrieve the animal. Terry was so shy that Spitz figured he could never train it to work in films but, in 1934, an MGM director familiar with Spitz’ kennel was desperate enough to try and use Terry in a Shirley Temple film. The dog performed beautifully and appeared in several subsequent movies but Spitz wasn’t sure the small, still somewhat timid animal could handle such a massive production. Upon entering MGM studios with the dog, Spitz was immediately escorted to the Thalberg building, where the entire pre-production crew was attempting to get the Wizard of Oz into filming as quickly as possible. Terry was practically cast on sight, with Spitz using non-verbal commands to get what became America’s most famous Cairn terrier through its usual tricks. Spitz’ only regret was that he did not realize how desperate MGM was, agreeing to a weekly salary of a mere $125 a week.

Bolger’s wrinkled burlap face was provided by a specially molded rubber mask that covered his head and neck with the exception of his nose, mouth and eyes. The mask had to be glued on daily, makeup then manually added to his visible nose and mouth. This process took two hours, necessitating Bolger’s studio arrival at 6:15 AM.

Lahr’s lion costume and makeup was even worse. The padded body suit he wore weighed ninety pounds, prosthetic devices were glued to his face that prevented him from eating anything that he couldn’t ingest through a straw.

Born Lazar Meir in the vicinity of Minsk, Russia, most likely on July 12, 1884, Meir emigrated to St. John’s, New Brunswick, Canada, with his parents and siblings, anglicizing his name to Louis Burt Mayer. A high school dropout at age 12, Mayer worked within his father’s junk and scrap metal business, crisscrossing St. John’s in a wagon and salvaging any scrap of value. At age 20, in 1904, Mayer moved to Massachusetts and continued in the scrap metal trade, subsidizing his meager income by hustling various odd jobs. Even as a young man in New Brunswick, Mayer was fascinated by vaudeville and show business, perhaps as an escape from an impoverished and gloomy existence. He scraped together enough money to buy a seedy burlesque house in Haverhill, Massachusetts and transformed it into a movie theater. Sensing that the motion picture business was on the cusp of widespread popularity, Mayer bought up additional theaters and formed a partnership to distribute films throughout New England. He paid D. W. Griffith $25,000 for the exclusive regional rights to show “Birth of a Nation,” typically without ever seeing the film himself, a deal which brought in four times the rights fee. Mayer also was interested in the production side of the film industry, establishing production entities first in New York and then in Los Angeles in 1918, where he formed his first production company, Louis B. Mayer Productions.

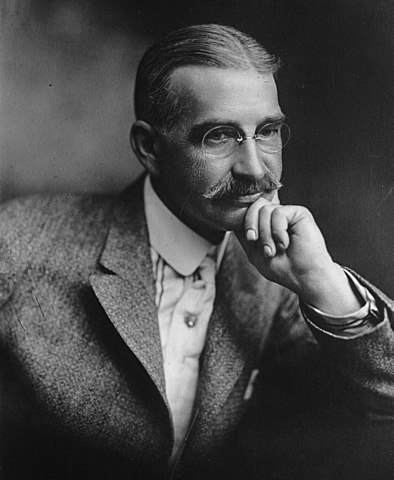

Long before the Wizard of Oz was produced as a film, the children’s novel written by L. Frank Baum had already achieved immense popularity. Born in 1856 in upstate New York, Baum’s background was typical of many American journeyman attempting to eke out a living in late 19th century America. Although interested in writing from an early age, he initially spent his twenties as both a member of a touring acting troupe as well as a salesman for his uncle’s carriage lubricant, Baum’s Castorine. Eventually tiring of these financially unproductive efforts, in 1888, Baum and his wife made the decision to move from Syracuse to present day Aberdeen, South Dakota. Initially a shopkeeper, when his store went bankrupt, he acquired and then began publishing and editing the local newspaper, The Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer. As a columnist, Baum expressed his views on various issues, including politics and current events but this venture was also a failure and Baum and his family returned to Chicago, where he was employed as a reporter for a large daily, the Chicago Evening Post. He also again supplemented his income as a salesman, but his enterprising mind continued to produce ideas involving creative writing.

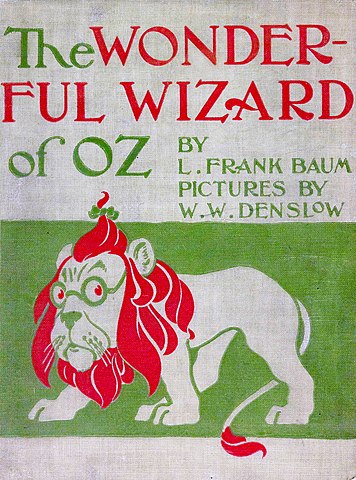

Baum made a deal with W. W. Denslow to illustrate the book, a 50-50 split, and the illustrations again broke new ground in children’s literature. By October of 1900, the book was well into sales of its second edition and a runaway success and Baum’s first royalty check in December of 1900 was for $3,000, approximately $100,000 today. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz remained the best-selling child’s book for more than two years after its release.

Oz resumed production on November 4, 1938, with director Victor Fleming. Fleming already had a reputation as MGM’s fixer of problem productions. His experience dated back to silent films, working for various directors including D. W. Griffith. He made stars out of Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Jean Harlow in the late twenties and early thirties. Having made a good living in motion pictures for many years, Fleming lived the high life on his twenty acre horse ranch in Bel Air, riding a motorcycle years before it was fashionable. As good looking as the men he directed he also carried on affairs with many of his leading ladies ranging from Clara Bow to Ingrid Bergman, finally marrying at age 34 in 1933. Although considered a breach of studio etiquette and the star system, Clark Gable routinely ate lunch with Fleming at the studio commissary, such was his respect for the director, also a close friend.

In an effort to bolster MGM talent behind the camera, Mayer poached one of Warner Brothers most esteemed producer-directors in Mervyn LeRoy. He secretly paid Leroy $6,000 a week, practically double what any other producer was making, although his salary did not remain secret for long. But LeRoy was a veteran of nine years at Warner Bros and well known as both a quality filmmaker and efficient professional.

Baum always envisioned Oz as the perfect backdrop for an amusement park and to pursue such a venture he moved permanently to Los Angeles, acquiring land in central Hollywood in what was then mostly orange groves, building an elaborate two story home he christened “Ozcot,” where he lived for the rest of his life.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS