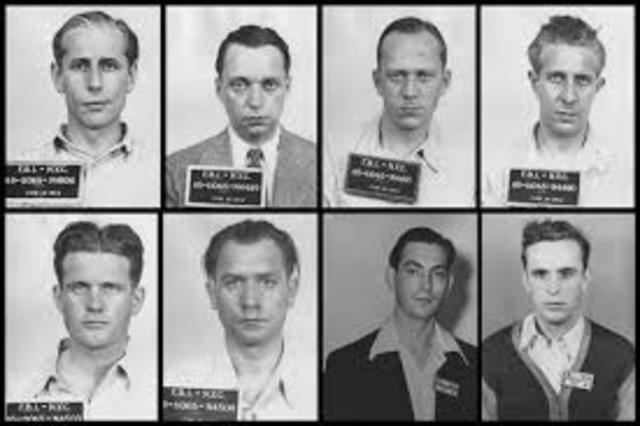

The true story of eight nazi spies who landed on American shores via U-Boat at the height of WWII

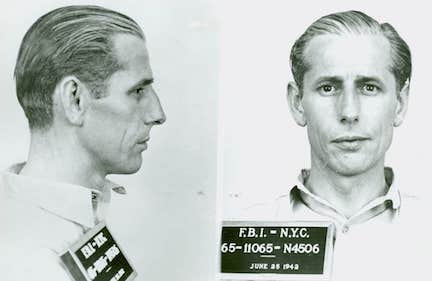

George John Dasch was born on February 7, 1903 in Speyer, Germany, the fifth of thirteen children. His mother, a social worker and quite influential at critical moments of his life, implored him at the age of thirteen to enter a seminary in preparation for the Catholic priesthood. Dasch was expelled a year later and then served briefly in the German Army at the conclusion of World War I, lying about his age to facilitate enlistment. Post war occupation by American troops resulted in Dasch’s fascination with emigrating to the United States and his employment on the docks of Hamburg allowed him to eventually stow away on a merchant ship bound for Philadelphia. There, he avoided detection and blended into the neighborhood, getting a menial job within days of his arrival in October of 1922. Determining that he might have more success within the large German ex-pat community in New York, Dasch quickly headed north.

All eight men were outfitted with American style civilian clothes, fake identity papers and presented with eight wooden crates containing waterproof stainless steel receptacles packed tightly with plastic explosives, detonators, and timers. Dasch and Kerlin as team leaders were given additional training in invisible ink composition and composed handkerchiefs covertly containing contact names for reliable friends and relatives in the US. Dasch and Kerlin were also each given approximately 85,000 dollars.

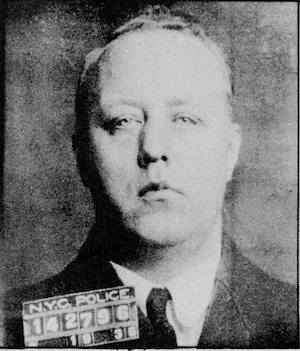

Upon arrival, Dasch was confined to a hotel with other newly arrived German nationals where he was rigorously interviewed by officials intent on determining the exact motivation for his return. Among these interviewers was a man named Walter Kappe, who grilled Dasch in English to assess how well the he spoke the language. After Dasch lied to him about employment in an import-export company and demonstrated language proficiency, Kappe gave him his card, indicating that he was an editor of a magazine and encouraged him to interview for a position. Dasch was polite, but was anxious to visit his family and explore other less nebulous options via family connections.

Hitler no longer had to worry about that consequence, and he began to berate Abwehr chief Wilhelm Canaris, to implement the Fuehrer’s concept of a massive covert attack on America, both destroying American industrial capability and fomenting a home grown fifth column of resistance within the German-American community.

By then, the four saboteurs were nowhere near Amagansett, although their exit from eastern Long Island contained some precarious moments. Dasch was vaguely familiar with the area and recognized the general location of Amagansett from his days living in New York, but he still had no clear direction for the village or railroad depot. The men were savvy enough to get away from the beach as quickly as possible and still under the cover of darkness, they were able to quickly access the main road in the area, the Montauk Highway. Wandering in a northerly direction and careful to avoid any homes or brightly lit areas, they were especially alarmed by the sound of the U-boat diesel engines they heard as they stealthily tried to extricate themselves from the beach vicinity. When a large campground forced them to walk in a circuitous manner, they stumbled over some railroad tracks. Dasch correctly headed west and within a mile they reached the Amagansett train station. At five o’clock on a Saturday morning, it was locked and deserted. All four men got rid of any wet clothes and tried to make themselves as presentable as possible. At six AM, the station opened and Dasch bought four tickets to New York, the first train leaving at 6:59. The four men were the only passengers to board at Amagansett and within minutes they were rapidly leaving the Hamptons behind, incredibly relieved to have successfully completed one of the most challenging parts of their mission. Heinck even shook Dasch’s hand, acknowledging his leadership in guiding them out of danger.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS