Few personalities have achieved the worldwide fame and popularity of Harry Houdini. Successful in several different media ranging from vaudeville to motion pictures, this performer was also an astute businessman who incorporated both groundbreaking copyright implementation and sensational publicity to establish himself as the first 20th century entertainment superstar.

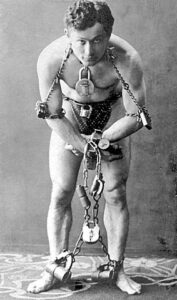

To garner publicity, Houdini now started to promote himself by slipping handcuffs in police stations after a meticulous search by detectives. In San Francisco, he stripped down to a veritable loin cloth to illustrate that he could not possibly be concealing a key or lock pick. Then police restrained him with at least ten of their own pairs off handcuffs, even going so far as fastening ankle shackles to the wrists with an additional set of cuffs. Houdini was then lifted up and placed in a nearby closet, emerging minutes later with each set of handcuffs removed and now attached together, the magician still practically naked. Publicity photos of Houdini’s scantily clad muscular frame, draped with all nature of restraints became commonplace. Because he could not perform in such a risqué costume, Houdini instead added the wardrobe obstacle of a straitjacket strapped over and under the numerous locks, cuffs and metal restraints he typically employed. This became another of the performer’s trademark routines.

Although Houdini himself provided intense drama for his audience, he personally experienced one of the most dramatic moments of his own life when his mother, Cecelia, died on July 17, 1913. Although all such mother-son relationships are typically close, Houdini had an especially strong maternal bond. Having become a worldwide success, the rock that his family and especially his mother relied upon and an attentive son who lived up to his vow to his dying father, Harry Houdini’s interaction with his mother was a typically Old World relationship. Unlike his behavior with non-family members, which was egotistical, controlling and financially ruthless, Houdini even described himself as a Mama’s Boy and it is has been speculated that his entire career and especially his death defying stunts were nothing more than an attempt to arouse approval, attention but most importantly Cecelia’s concern.

However, the nineteen year old was anything but an overnight success. He first paired himself with an acquaintance factory co-worker and briefly with two of his brothers, most notably his younger brother, Theo, nicknamed Dash from his middle name of Dezo. Eventually, Dash would strike out successfully on his own, performing as Hardeen, but Harry Houdini’s co-performer by then was Wilhemina Beatrice Rahner, nicknamed Bess, who also became Houdini’s wife in mid-1894. Bess came from a German Catholic background, an unusual union within such a devoutly Jewish family. All of the relatives eventually accepted the marriage and Bess became an integral part of Houdini’s act.

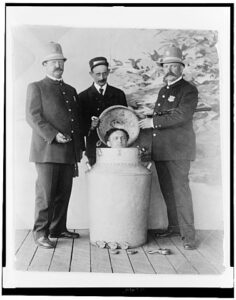

What resulted was one of his most famous tricks, the milk can escape. Onstage, Houdini had audience members kick the four foot tall can to establish that it was in fact metallic and inflexible. The can was then filled with water while offstage Houdini changed into a bathing suit. When he returned, he was handcuffed and placed inside of the can after telling the audience to hold their breath for as long as they could. Six hasps secured by locks, some even provided by spectators, were then secured and a screen was placed in front of the can, this process itself taking approximately a minute. Houdini’s assistant, Franz Kukol, an Austrian hired while Houdini performed in Europe, stood by with an axe, the audience told that he was to break open the can if Houdini did not emerge in a set amount of time, the Austrian’s presence designed to add additional tension to the already potentially fatal undertaking. Houdini did employ a remarkable ability to hold his breath, as a young man he is said to have been able to do this for 3 minutes 45 seconds. But on a regular basis he was able to not breath for about two and a half minutes, more than enough to take advantage of one aspect of his specially designed enclosure. The so called milk can had rivets on it that were in fact fake. Although anyone examining the top of the can who tried to pull it off would not be able to do so, anyone inside the can could quickly and easily push the top part of the can off with the locks still in place, put the top back on and in Houdini’s case easily slip out of his handcuffs. He typically emerged in about three minutes, soaking wet, but free of his cuffs, having seemingly defied death in an inexplicable manner.

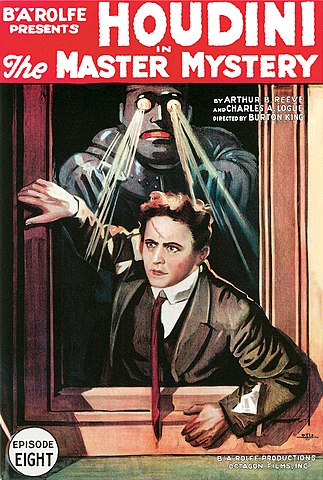

Having received numerous challenges from various individuals incorporating Asian themed restraining devices, Houdini wished to adapt these exotic components within the ultimate escape challenge. What resulted was the Chinese Water Torture Cell, an elaborate specially constructed glass, telephone booth sized container into which Houdini was lowered headfirst, his feet locked into wooden stocks. But, before he even performed this trick in front of a live audience, Houdini attempted to anticipate any of the inevitable copycats who might attempt something similar. Understanding that patents did nothing to stop any of his imitators who merely slightly varied any devices or performances to circumvent such restrictions, he instead performed what he eventually described as a one act play which he called Houdini Upside Down. This performance deliberately took place in front of an audience of one individual, Houdini then able to copyright it and its contents, asserting that only he had the legal right to perform such a trick. Granted an official copyright by the Lord Chamberlain, entertainment managers were then formally notified of this legal perspective, warning them of consequences if this alleged intellectual property was infringed.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS