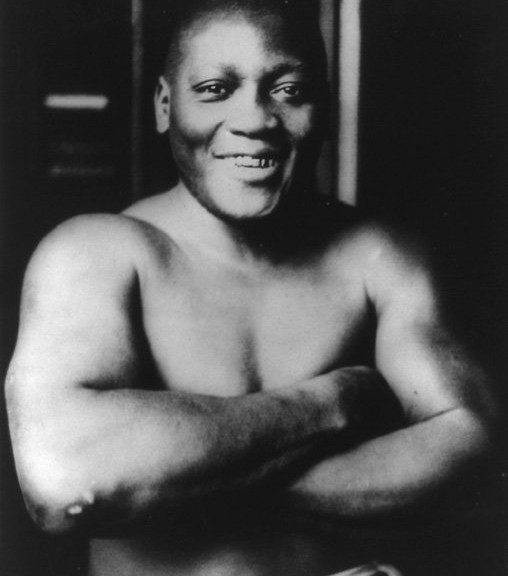

Jack Johnson, the Real Deal

Jack Johnson was born on March 31, 1878 in Galveston. Very little can be verified about his early life. Most historical information about him comes from autobiographies that he published himself. Had he not gone on to achieve boxing notoriety, both he and his family would have been completely forgotten.

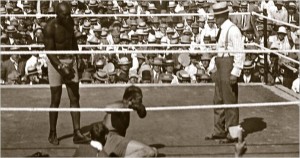

By the end of the fourteenth round Jeffries could barely see, his nose was broken and face and upper body streaked with his own blood. He lumbered gamely toward Johnson at the beginning of the fifteenth round, attempted to clinch but was too exhausted to avoid Johnson’s repetitive combinations. Finally, perhaps attempting to avoid punishment, Jeffries turned away from Johnson and lurched awkwardly along the ropes. Johnson responded with a string of rights and lefts that put Jeffries on the canvas for the first time in his pro career. The stunned crowd watched as Jeffries got to his feet, literally with the help of spectators, but was immediately knocked down by a more direct punch that put him back on the canvas. Boxing rules at that time allowed a fighter to stand over a fallen opponent and hit him as soon as he got up. Rickard attempted to shield Jeffries for a brief moment but when the defenseless fighter staggered to his feet, Johnson draped him on the ropes with another succession of brutal punches. Jeffries corner men stormed into the ring, one tossed a towel in Jeffries direction. The fight was over.

Within days of signing the contract, Jack Johnson would attend Long Island’s Vanderbilt Cup auto race. Although he would barred from the finish line reviewing stand where he was told that no blacks were allowed, he would meet Mrs. Etta Terry Duryea, an elegant, very attractive Caucasian female currently separated from her socially well connected husband. Mrs. Duryea was clearly a cut above the usual women in Johnson’s entourage. While the two promised to keep in touch, Johnson spent the interim between his fight with Jeffries on a vaudeville tour of the Midwest and northeast.

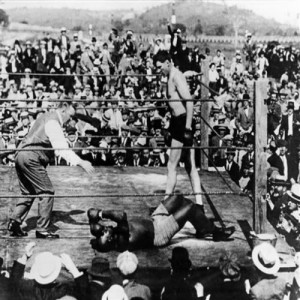

By the twenty first round, Johnson was still scoring but he had not hurt Willard and his usually confident demeanor had disappeared. There were no smiles or taunts as Johnson’s thirty-seven years and grueling lifestyle seemed to be catching up with him. In the twenty-fifth round Willard landed a punch to the body that made Johnson gasp audibly and the challenger was visibly the quicker, fresher fighter. When the bell rang for the twenty-sixth round Willard quickly hit Johnson with another right to the body that had Johnson desperately trying to clinch but the challenger shrugged him off and feinted for a few seconds before unleashing a pulverizing right that landed flush on the jaw. Johnson began falling to the canvas and tried to grab Willard unsuccessfully. He landed on his back, both of his arms extended over his face as the referee counted him out. The fight was over, the heavyweight championship of the world had changed hands.

On Monday, June 9, 1946 Jack Johnson was returning to New York by automobile from a stint in a Texas tent show. These were the types of appearances that he essentially survived on in the last twenty-five years of his life. He was near the town of Franklinton, North Carolina, driving his Lincoln Zephyr at over seventy miles an hour when he lost control and hit a telephone pole. His assistant was thrown from the car and survived, Jack Johnson died in a hospital three hours later.

Jack Johnson’s funeral was held in a Baptist church in his mother’s old neighborhood and attended by twenty-five hundred spectators and thousands more milling outside. He was buried next to Etta Duryea in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery, resting place of some of the city’s most prestigious citizens including Potter Palmer, Cyrus McCormick and Marshall Field.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS