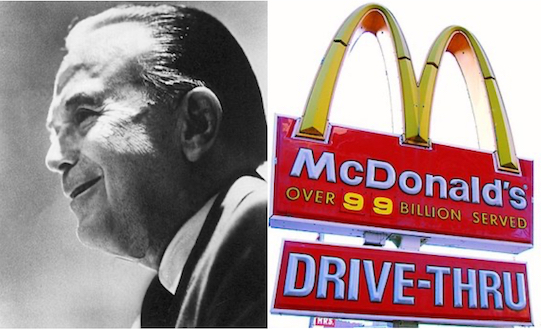

In July of 1954, an obscure milk shake mixer salesman walked into a fast food restaurant in San Bernardino, CA. The restaurant was operated by two brothers named McDonald, the result of this interaction profoundly changed American culture, business and nutrition forever.

Ray Kroc first interacted with Prince Castle as the Chicago based account manager for Lily-Tulip and sensing the enormous potential of the Multimixer device, he secured the national distribution rights for the machine in 1939. For two years he rapidly increased sales, his customers mostly the corner drug stores and soda fountains that were a mainstay of urban America.

Just as Kroc began to build national momentum for his sales distribution company, America entered World War II, a development that cut off two staples necessary for his continued growth. Civilian access to copper, a critical element of his Multimixer motors was halted, any supplies of this metal earmarked for military consumption. Sugar was also heavily rationed so that products like ice cream were virtually unavailable during wartime. Rather than shutting down, Kroc improvised, determined to tough it out until the end of the war. He found two additive products, consisting of mostly corn syrup and a chemical stabilizer that when mixed with chilled milk resulted in something that mimicked ice cream.

The McDonalds were not even the first to market specialty hamburgers in southern California. In 1937, a Glendale, California owner of a drive-in restaurant , Robert Wian, invented a double decker hamburger sandwich slathered with various condiments and toppings that was so successful, he called it the Big Boy, and prompted a restaurant name change to Bob’s Big Boy, eventually another successful nationwide hamburger chain. The McDonalds brothers would impact the rapidly evolving American fast food landscape by implementing some concepts that were, at the time, revolutionary. Although quite successful, their drive-in restaurant incorporated the car-hop delivery system, in which individuals, usually teenaged females offered curb or parking lot service on a tray, which was popular with teenagers but turned their location into a hangout where the parking lot was filled with leather jacketed youngsters who took up space for hours and also alienated older families with children who did not like such an atmosphere.

It was in early 1954 that Kroc decided that at the very least, to try and buck up his sales numbers, he wanted to learn more about a restaurant run by two brothers in San Bernadino, California who had ordered ten Multimixers for their small Southern California location. He even asked his West coast rep how such a small restaurant could need enough machines to prepare as many as sixty shakes at a time and then decided he would go see for himself. If nothing else, this restaurant was generating orders from other hamburger joints that were trying to copy this business, called McDonalds, to duplicate their wild success.

As the carhop-hangout atmosphere dissipated, working class families began to descend on the restaurant in greater numbers, eating at a restaurant now a viable economic alternative. Children also enjoyed going up to the window, ordering and then bringing back the food to their car, all under the watchful eyes of their parents, a lesson in independence. The building itself was different with an octagonal shape and glassed in design from the roof to the countertop, the always immaculate kitchen, with its stainless steel, grills and efficient employees a revelation to most customers who had never set eyes on a restaurant’s interior. On the roof was a huge neon sign with the MacDonald’s name, and their mascot Speedy, the symbol for what they dubbed the, “Speedy Delivery System.” Within a year, the restaurant regained the same volume it had before its realignment. It further streamlined its production line process with customized tools, and extremely specific guidelines. And, perhaps to maintain a focused, completely businesslike approach, especially among younger employees, only males were hired. McDonalds mushroomed into a high volume, unique operation with eventually spectacular results.

Ray Kroc was also not the first individual to discuss potentially franchising the McDonald’s name and concept. In fact, by the time Kroc approached them the brothers had actually sold fifteen franchises. Well, sort of. What they sold was a manual describing the Speedy Delivery Service, some building plans, one week of training with a store manager and the McDonald’s name for a fee of $1,000. They specifically did not provide any financial or business connection on any ongoing basis, the franchisee strictly on their own. Even this process was something that Mac and Dick did not pursue aggressively.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS