The remarkable story of the courage and suffering of the passengers aboard the Mayflower and the establishment of the Plymouth Colony.

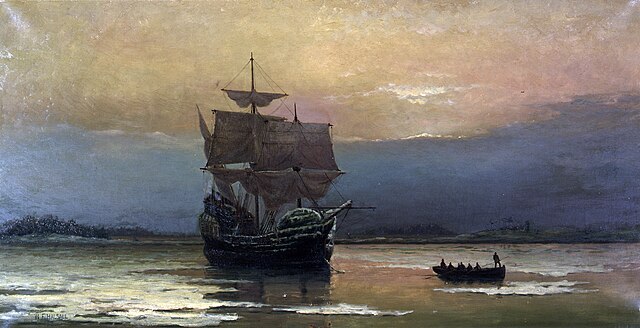

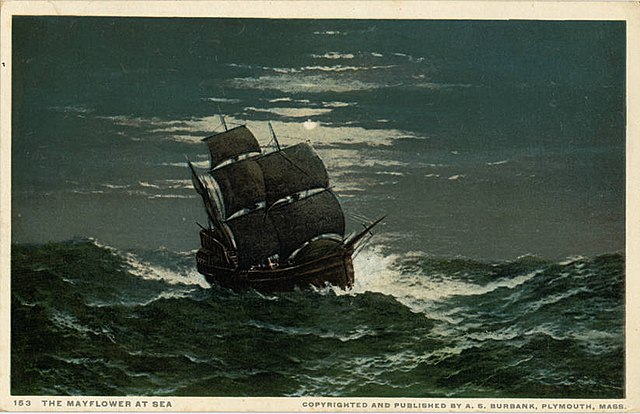

On November 11, 1620, a 100 foot long cargo ship called the Mayflower entered what is today known as Provincetown Harbor, virtually on the tip of present day Cape Cod. This was the culmination of over two months at sea for 102 immigrants, originally from England, some of this contingent intent on establishing their own religious settlement in the New World, free from persecution from the British crown. Their Atlantic crossing was difficult, their time spent mostly below deck, lashed by gale driven waves that left them and their clothes and quarters in a miserably damp and chilly condition, their diet of hardtack, dried meat and watered down beer little comfort.

William Bradford was born in March of 1590, in Austerfield, Yorkshire, England. The exact date is unknown although he was baptized on March 19 of that same year. Many members of his family died when he was a child, and Bradford was orphaned by the age of seven. Sent to live with two uncles, he spent most of his time as a farm laborer and his leisure activity consisted of reading and studying the Bible and other classic philosophical tracts. Intellectually curious, he was exposed to various sermons of area preachers who radically suggested that the Church of England was still inappropriately influenced by Catholicism.

Figuring he couldn’t just abandon the Billington boy, Bradford ordered ten armed men, including Edward Winslow, to load up the small sailing ship used during exploration, take Squanto and another native interpreter, Tokamahamon and head to eastern Cape Cod and Nauset territory. A storm forced the boat to come ashore at what is now Barnstable, Massachusetts, on the northern shore of the Cape, about halfway across the lower portion of the peninsula.

The passengers were situated on the deck immediately located underneath the open air of the main deck. While they could hear waves and smell sea water, they were unable to view the horizon or the surface of the sea around them. Tossed practically on top of each other in makeshift compartments created by cloth curtains, the Separatist contingent strived to get along with each other, realizing that the stress of the voyage would only be increased by personality conflicts.

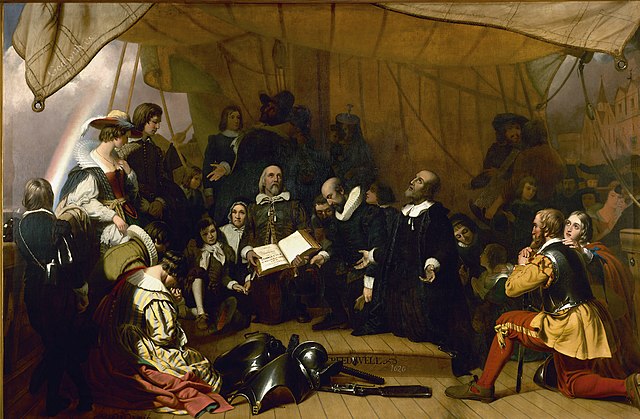

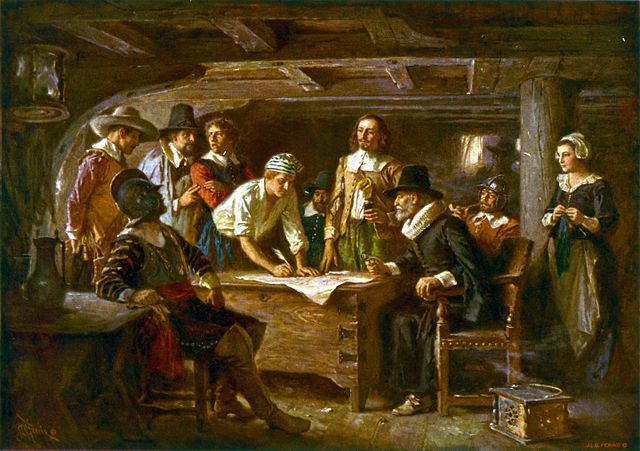

This premature landing outside of territory designated by British authorities presented an immediate problem. Since the Stranger contingent on board was inclined to dispute any attempts at the Separatists controlling the governance of the colonists once they landed, assertions were made that as a result of the ship landing in an undesignated territory, they were free to do as they wished and were not obliged to respect any other authority. To address this situation several charismatic individuals on board the ship composed an agreement that set out specifically what laws and guidelines should be followed by the community. Containing ideas generally suggested mostly by William Brewster, this agreement, known historically as the Mayflower Compact also resulted from some of the formerly aloof Strangers like Christopher Martin understanding that for the colony to financially succeed and for the Adventurers to get any kind of return on their investment, all of the Settlers needed to work together.

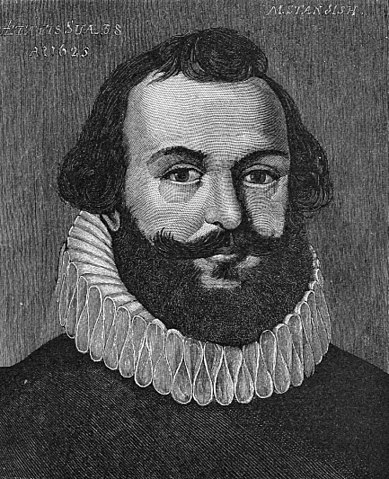

Among some of the men on board, including Bradford and Miles Standish, an experienced soldier officially in charge of matters involving potential conflict with natives or even obstreperous settlers, there was a great impatience for some kind of organized exploration of the nearby territory.

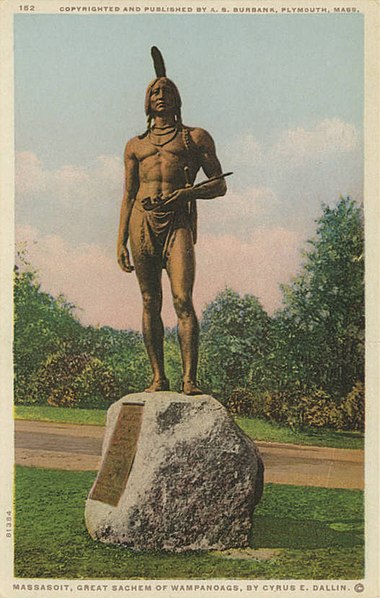

Samoset identified the area as under the control of Massasoit, the Sachem or leader of a tribe known as the Pokanokets, and today as the Wampanoags. Massasoit resided in the nearby Narragansett Bay area of Rhode Island.

Although this festival was the impetus for the national American holiday known as Thanksgiving, the colonists at Plymouth would not have referred to their planned, three day event by that name, a term they applied instead to a much more serious religious rite acknowledging gratitude to the almighty. Instead, they celebrated with games, military exercises and vast amounts of food and drink. Only four adult women, including Susanna White Winslow were still alive to help cook the meal, along with their daughters and a few servants.

Although on a daily basis, life continued to be harsh and frequently unforgiving, by the end of September, settlers at Plymouth Colony seemed to have turned a corner. They concluded the first harvest of all of the crops that they meticulously planted earlier in the Spring. Corn, Squash, Beans and even some amounts of barley and peas were stockpiled, a plentiful contrast to the dreadful deprivation of the previous winter. As massive flocks of ducks and geese migrated through the area, the settlers were able to hunt down as many of these birds as they wished, again putting aside a large quantity to help celebrate a tradition that was centuries old, a harvest festival, consisting of food, drink and good cheer. But this festival was also an acknowledgement of their special gratitude to their original ally, Massasoit, who Bradford described as arriving with five deer, oysters, a hundred participants and another addition to the festivities, wild turkey.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS