The remarkable story of the courage and suffering of the passengers aboard the Mayflower and the establishment of the Plymouth Colony.

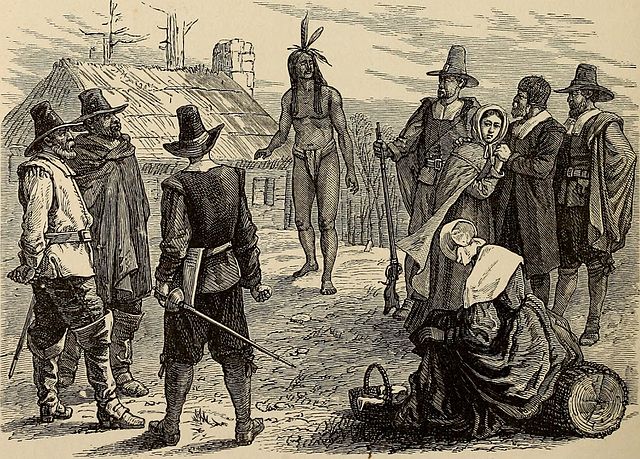

On March 16, the inevitable occurred, although the incident did not unfold as the settlers previously feared. As described in a pamphlet entitled, “Mourt’s Relation,” a description of the first year of Plymouth Colony, co-written by William Bradford and another settler named Edward Winslow, with work suspended for a regularly scheduled meeting about specific plans for the defense of the settlement, the meeting participants became aware of a native looking down at their group from a nearby hill. This had happened previously, but whenever an inhabitant gestured or even attempted to make contact with these previous visitors, the natives fled. This time, however, the lone native began to purposefully walk directly towards the settlement. Without hesitation, he walked past the crude lane of houses and seemed headed directly towards the shelter that protected the colony’s women and children during such an emergency. Without overt hostility, some of the armed settlers got in his way and made it clear he could not enter the shelter. Instead of bristling or running away, this remarkably tall, long haired individual dressed only in an animal skin loin cloth stood to his full height, saluted and probably understanding the effect he would elicit cheerfully spoke the words, “Hello, English!”

Sunday was of course another leisurely day, but on Monday, they began to reconnoiter the harbor in earnest. It was certainly deep enough for a ship the size of the Mayflower, and eventually, upon landing on shore they found large areas suitable for agriculture, fresh water in several streams and no obvious signs of any kind of recent habitation by natives. Additionally, although at least one sizable boulder was certainly situated in the area, there was no mention by Bradford in either of his two personal accounts of this excursion of a landing assisted by a large rock. This seems to have been an invention of subsequent residents, much to the delight of future chambers of commerce. Today, an elaborate, arched, templelike edifice encloses a rather unimpressive large rock embossed with the date of 1620, the alleged landing spot of America’s Pilgrims.

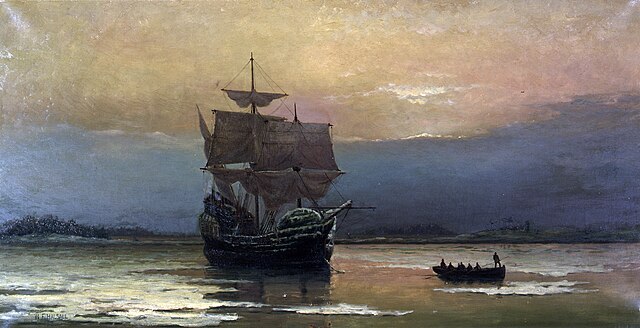

With the onset of Spring and milder weather, the establishment of at least an initial footprint of a settlement and the astonishing new relationship with a powerful local ally, Captain Christopher Jones decided that this was the appropriate time to sail back to England. After all of its cargo was removed and brought ashore, rocks were added for ballast and, on April 5, the Mayflower slowly made its way out of the harbor, an introspective moment for all of those left on shore. Because of the seasonably calm weather and westerly prevailing winds that propelled the ship instead of impeding the craft, It took only a month for the Mayflower to reach its home port and Jones’ residence on the outskirts of London at Rotherhithe. For a brief period he and his ship continued to participate in transporting goods like sugar between England and neighboring countries across the English Channel. But Jones’ health, permanently impaired by his Atlantic crossing with the Plymouth settlers, was undermined to the extent that he died on March 5, 1622, less than a year after returning from North America. The ship remained unused for two years, tied up in the Thames near Rotherhithe. Without proper maintenance, it fell into disrepair and eventually its owners which included Jones’ widow, applied for an official valuation from the Admiralty, which came to a little more than one hundred pounds. There are no substantiated accounts as to what happened after the ship was dismantled, the most appealing suggestion that the timber from the ship eventually was used to construct a barn in the county of Buckinghamshire. For many years this structure was presented to tourists as a Mayflower relic, today it is closed to the public, its historical provenance suspect.

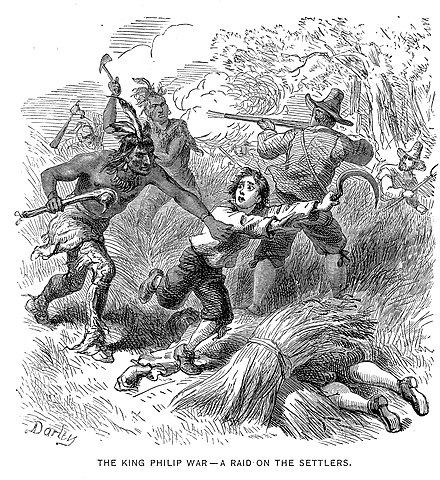

The belief that Wamsutta was poisoned was one of the fundamental grievances that eventually contributed in 1675 to one of the most violent and costly native rebellions in US history. One of Metacomet’s military opponents was Josiah Winslow, then governor of Plymouth colony and the son of Edward Winslow. At its conclusion, three years later, dozens of colonial New England settlements lay in ruins and thousands of settlers were killed or injured.

Although he waited until the Spring, Standish resolved to preemptively extinguish the threat before any such attack. In late March of 1623, he invited several powerful native warriors and sachems to participate in negotiations to resolve their complaints. Instead, when this meeting occurred, and upon serving large amounts of food and alcohol, the most prominent natives present, Wituwamat and Pecksuot and another warrior were attacked, Standish grabbing the knife from around Wituwamat’s neck and personally stabbing him repeatedly in the chest, killing him. Wituwamat’s teenage brother, who was waiting in the vicinity was also subdued and subsequently hanged. Wituwamat was then beheaded and his head stuck on a pike at the main entry gate at Plymouth Plantation. The residents of Wessagussett either sailed the Swan to fishing villages in Maine or relocated to Plymouth.

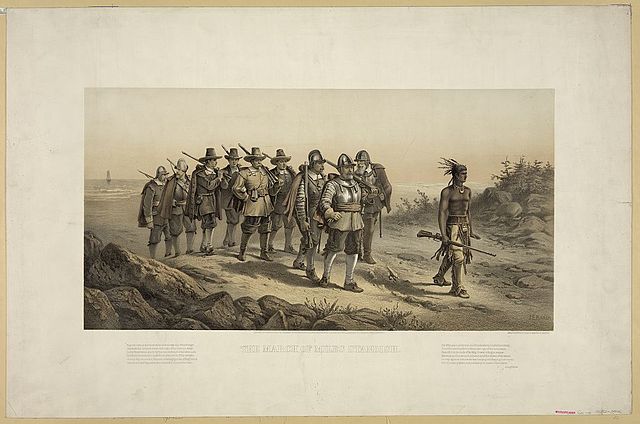

Myles Standish also lived into his seventies, his military position serving Plymouth Plantation ending around 1635. By then he and others had successfully negotiated with the Merchant Adventurers to retire their debt, Standish receiving a 120 acre farm in the area known today as Duxbury, Massachusetts. He subsequently served in various Plymouth Colony administrative positions, including as a kind of superintendent of highways until his death in 1656, aged 72.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS