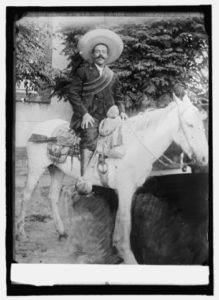

Of the many political figures involved in Mexico’s 1910 Revolution, Pancho Villa remains the most famous and charismatic.

Like the history of Mexico itself, Villa’s early life and biography is obscured or disputed. Much of the information about Pancho Villa came from his own self-serving autobiography or biased journalism and glorifying newsreels from the time period. What is generally accepted is that Villa was born Doroteo Arango to a sharecropper father and domestic mother on June 5, 1878, in San Juan Del Rio, in the Mexican state of Durango.

In 1910, Mexican President Porfirio Diaz was re-elected to his seventh term as the political leader of the Mexican government. Diaz had served as President for 30 of the previous 34 years, so politically powerful that this entire time period is referred to historically as the Porfiriato. Although Mexico’s economy experienced expansion and prosperity during Diaz’s reign, much of the increased international trade, railroad construction and economic infrastructure was financed with European and American capital and benefited foreign entities and individuals and a small group of Mexican elites to the detriment of most of the Mexican population, who barely survived in squalor and deprivation.

Madero had no choice but to employ the reactionary general Victoriano Huerta as the head of the column that headed north to Chihuahua to challenge Orozco. He also personally requested that Villa join the general to oppose Orozco, an overture that Villa accepted. In command of 4800 federales, General Huerta accepted Villa’s men into his fighting force strictly out of necessity, considering Villa a glorified bandit.

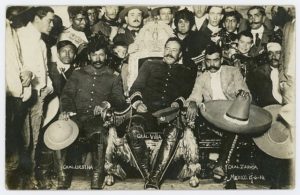

Pancho Villa chose this window of opportunity to march his army within a few miles of Mexico City, pausing only to meet personally with Zapata. On December 4, 1914, at Xochimilco, one of the more remarkable meetings in Mexican history occurred when the two men met and came to an agreement as to carving up territory and future military strategy. Two days later, both men’s armies entered the capital, Villa providing Zapata’s forces with weapons and artillery. Obregon had already declared his opposition to Villa and after assassinating some of his longtime political enemies, Pancho decided to leave attacking Veracruz to Zapata and headed North, to consolidate his power in the region.

Because Carranza had support throughout the country, Villa was forced to defend territory that he previously controlled. Both Villa and Zapata abandoned Mexico City, which was then immediately occupied by Obregon. The Carrancistas took everything of value and added more recruits from the poorest sectors of the city, the only alternative within the looted capital was starvation. Villa focused on a long term offensive with an objective of pushing all of the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Francisco Madero was elected President of Mexico in October of 1911, Diaz having left the country for exile in France. But the united hostility that combined many elements of a rebellion against the Porfiriato now focused their antagonism on Madero. For his part, Pancho Villa was relatively inactive during this time period. He was now amnestied from any possible political or criminal prosecution, had a substantial group of armed supporters to insure his security and looked forward to enjoying a period of relative solitude. Unfortunately, Mexico’s political atmosphere remained chaotic. In the South, rebels under the command of Zapata continued to seize territory and property, especially when it was clear that land reform was not imminent. Madero was forced to use the national army to stabilize the situation and achieve at least a stalemate.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS